Citing this biography: Boyd, Michelle, "Johann Adam Knoll and Catherina Pfeifer," article, Olive and Eliza, last accessed [current date]."

Johann Adam Knoll was born 21 October 1832 in Herzog, Samara, Russia to Gregorius Johannes Knoll and Elisabetha Jaeckel. He was baptized 22 October 1832.

Adam married Katharina Pfeifer 28 October 1852 in Herzog, Samara, Russia. Katherine was born 24 November 1832 in Herzog, Samara, Russia to Johann Adam Pfeifer and Justina Katharina Billinger. She was baptized 25 November 1832.

In 1874, a law was passed, requiring military service of the colonists, despite Catherine the Great’s prior grant of exemptions to the German settlers. That spring, about 3,000 colonists met at Herzog and determined to send delegates to America to investigate the possibility of resettling there. That November, four men in Herzog were drafted as soldiers and others were drafted in another colony that December. The need to leave Russia became urgent. However, they could not just leave. Besides needing both a two-thirds vote of the Gemeinde (the heads of families), anyone desiring to emigrate needed a pass from the governor.

The Knolls were part of the largest group to set off from Herzog and vicinity. They faced delays and “some gifts to the governor” were made until all but four of 108 families had secured passes to leave. The four families denied passes were those of the men who had been drafted. Attempts were made to petition both the war department and minister of war, but to no avail. According to Laing, “As a last resort a telegram was sent to the czar and arrangements made to delay the answer so that it would reach the colony only after all had passed the Russian border.”

The group left Saratov in June or July 1876, taking up seventeen coaches (later being joined for a time by a group of Mennonites, who took up another ten coaches). After arriving at Chernyshevskoe (also called Eydtkuhnen), the group separated and the Knolls went with the group that arranged passage through the North-German Lloyd to Bremen, Germany, then New York.

The Knolls arrived at Castle Garden in New York City aboard the Mosel on 29 July 1876, which had departed from Bremen, Germany. On 3 August, they arrived by train at the newly founded Herzog (later called Victoria), Ellis, Kansas, and on 16 August, Adam filed a homestead application for a farm northwest of Victoria. According to Anna Knoll, "After their arrival, they did what other settlers did. They proceeded immediately to build a shelter in the village, and within thirteen days, Adam Knoll applied for a homestead, so he would be able to farm as he did in Russia." Two weeks later, they completed a sod house on their homestead (establishing residency there five days later), then built a stable, dug a well, broke sod, and began raising crops. Adam also found work on the railroad, as he was not making enough money on the homestead. His three elder sons worked on the farm and elsewhere and his youngest, Peter, helped when he was old and went to school.

Adam became a naturalized citizen of the United States on 10 March 1883. This allowed him to become the owner of his homestead, which was patented in his name on 20 November 1883. As Anna Knoll claims, this made “Adam Knoll the first U.S. citizen to receive title to this tract of land from the U.S. government.”

In the summer of 1897, Adam, Catherine, and their four sons and their families moved to St. Peter, Graham, Kansas.

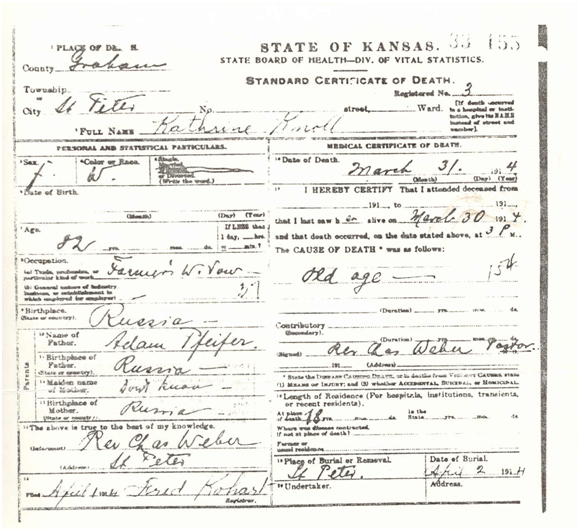

Adam died 14 November 1901. Catherine died 31 March 1914 in St. Peter, Graham, Kansas and was buried 2 April. They are both buried at St. Anthony Cemetery in Graham county, Kansas.

Adam and Catherina’s children are:

| 1 | Elisabetha

Knoll, born 2 Dec 1854 in Herzog, Samara, Russia, baptized 3

Dec 1854, died 25 Jun 1855 in Herzog, Samara, Russia of a fever. |

| 2 | Johannes Andreas Knoll,

born 17 Oct 1856 in Herzog, Samara, Russia, baptized 18 Oct 1856,

died 9 Dec 1857 in Herzog, Samara, Russia of a fever. |

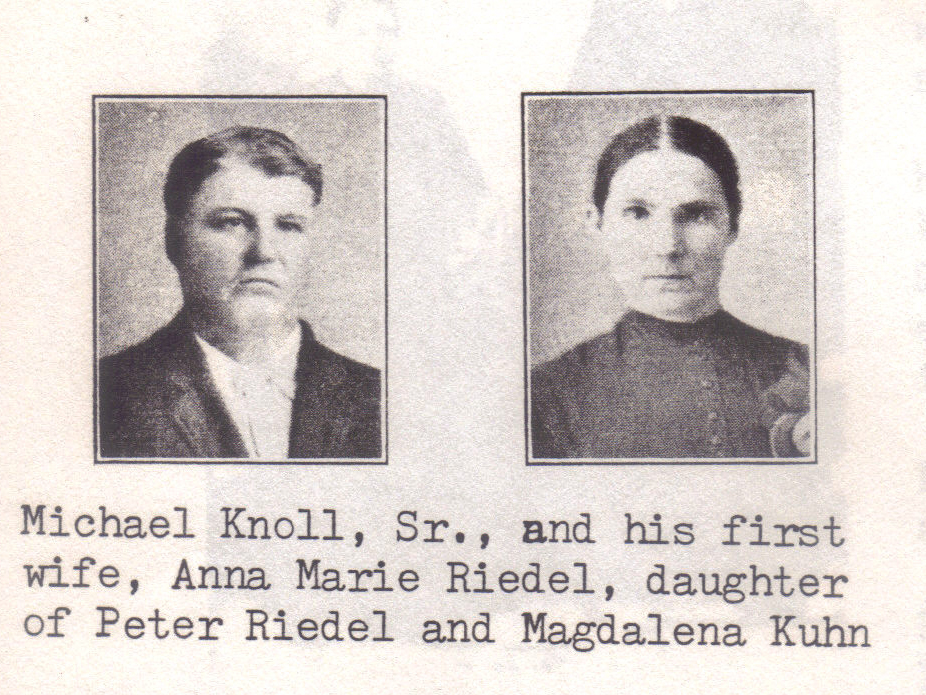

| 3 | Michael Knoll, born 1

Feb 1861 in Herzog, Samara, Russia, married 1) Anna Maria

Riedel in 1878 in Victoria, Ellis, Kansas, lived with his

parents, wife, baby daughter, and younger brothers in Herzog,

Ellis, Kansas in 1880, a farmer living in Bryant, Graham, Kansas

in 1900, 1910, 1920, and 1925, lived in Bryant in 1930 and 1940

(no occupation listed), married 2) Anna Mary Dietz, died 7

Jul 1941, buried in St. Anthony Cemetery, Graham county, Kansas. Both of his wives seem to have been recorded as Emma, Amma, and/or Ammie on censuses. This may be how the census takers heard Annamaria or may be a diminutive of the name. Wife 1: Anna Maria Riedel, b. 8 Sep 1862, immigrated to the US in 1876, d. 16 Oct 1901, bur. St. Anthony Cemetery, Graham county, Kansas. Wife 2: Anna Mary Dietz, b. 1860, m. 1) -- Bender, d. 1945, bur. St. Anthony Cemetery, Graham county, Kansas. Children (by Anna Maria Riedel): Barbara Knoll, Michael Knoll (m. Katey --), Margaret Knoll, John Knoll, Peter Knoll, Andrew Knoll, Clara Knoll, Beata Knoll, and Catherine Knoll (m. Joseph Billinger). Anna Maria was listed as having 10 children, 9 living in 1900, so there is one child unaccounted for in this list. |

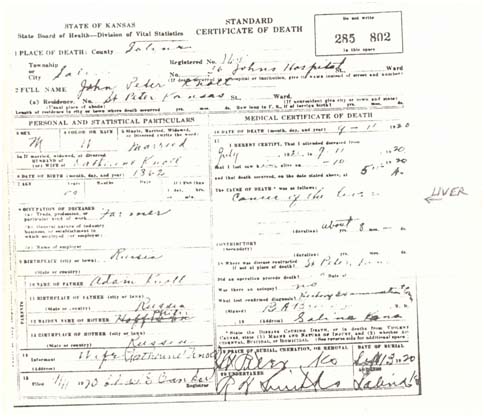

| 4 | John

Peter Knoll, born November 1862 in Herzog, Mariental,

Samara, Russia, a farmer living in his father's household in

Herzog, Ellis, Kansas in 1880, married Katherine Hoffman

20 June 1887 at St. Fidelis Catholic Church in Victoria, Ellis,

Kansas, lived with his parents in Victoria, Ellis, Kansas in 1895,

moved to St. Peter, Graham, Kansas in 1897, a prominent

farmer in St. Peter, illiterate but able to manage his farm

well, lived in Bryant, Graham, Kansas (living next to his parents)

in 1900, 1910, and 1920, lived in a sod house on a hill on the

south side of the road a half-mile to a mile from town, replaced

it with a frame one in 1903, also owned land to the east of St.

Peter and then bought the adjoining section, inherited 80 acres

from his mother, lived in Bryant, Graham, Kansas in 1905, died 11

Sep 1920 of liver cancer in St. Peter, Graham, Kansas, buried 14

Sep at St. Anthony’s Catholic Church in St. Peter. Wife: Katherine Hoffman, b. 20 March 1867 in Graf, Mariental, Samara, Russia to Johannes Hoffman and Anna Eva Schönberger, ch. 23 March 1867 in Rohleder, Mariental, Samara, Russia, came to America at the age of 17 by herself, d. 8 Oct 1924 in St. Peter, Graham, Kansas, bur. 11 Oct at St. Anthony’s Catholic Church in St. Peter. Children: Michael Knoll, Peter John Knoll (m. Rosa Gable), Anna Barbara Knoll (m. Willibald Braun), Michael John Knoll (m. Mary M. Braun), Anna Katherine Knoll (m. Jacob L. Dreiling), Andrew Knoll, Adam John Peter Knoll (m. Agrippina Weigel), and Rose Catherine Knoll (m. Jacob John Mahler), probably two other children. |

| 5 | John A. Knoll, born

Jun 1864 in Herzog, Samara, Russia, naturalized in 1882, married

1) Elizabeth Dinkel 20 Oct 1885 in Victoria, Ellis,

Kansas, a farmer living in Victoria Ellis, Kansas in 1895, a

farmer living in St. Peter, Graham, Kansas in 1900, 1910, 1915 (no

occupation noted), and 1920, lived in Bryant in 1930 (no

occupation), married 2) Christina Kessler 26 Aug 1895, 3)

Anna Maria Asselborn 15 Nov 1921 in St. Peter, Graham,

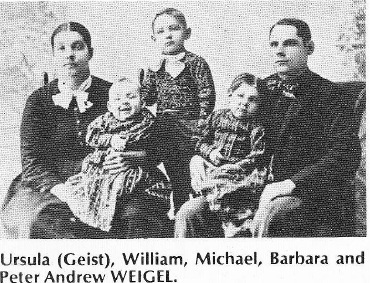

Kansas, and 4) Ursula Geist, died in 1936, buried at St.

Anthony Cemetery, Graham county, Kansas. Wife 1: Elisabeth Dinkel, b. Jan 1870, lived in Victoria, Ellis, Kansas in 1880 to George and Margaret Dinkel, d. 1895, bur. St. Fidelis Cemetery, Victoria, Ellis, Kansas. Wife 2: Christina Kessler, b. 1863, immigrated to the US in 1888, m. 1) -- Meier, naturalized in 1895, d. 1920, bur. St. Anthony Cemetery, Graham county, Kansas. Wife 3: Anna Maria Asselborn, b. 11 Nov 1861 to John Asselborn and Catharina Sterz, immigrated to the US in 1891, married 1) Andrew Schreiner, lived in Bryant, Graham, Kansas in 1910 and 1915, d. 24 Jul 1935 in St. Peter, Graham, Kansas, bur. 26 Jul 1935 at St. Peter, Graham, Kansas. Her epitaph reads, "She was the sunshine of our home." Wife 4: Ursula Geist, b. 2 Aug 1874, immigrated to the US in 1876, m. 1) Peter Andrew Weigel, lived in Herzog (Victoria), Ellis, Kansas in 1900, 1910, 1920, 1925 (as a widow), and 1930 (as a widow), d. 4 Dec 1943, bur. Sacred Heart Cemetery, Emmeram, Ellis, Kansas. Children (by Elisabeth): Catherine Knoll, Margaret Knoll, and Emma or Amy Knoll. Children (by Christina): Adam Knoll, Gottfried Knoll (m. Barbara --), John Knoll, and Carl Knoll. |

| 6 | According to family records,

Adam Knoll, born about 1866 in Herzog, Samara, Russia, died

in Herzog, Samara, Russia. |

| 7 | According to family records,

Elizabeth Knoll, born about 1868 in Herzog, Samara, Russia,

died in Herzog, Samara, Russia. |

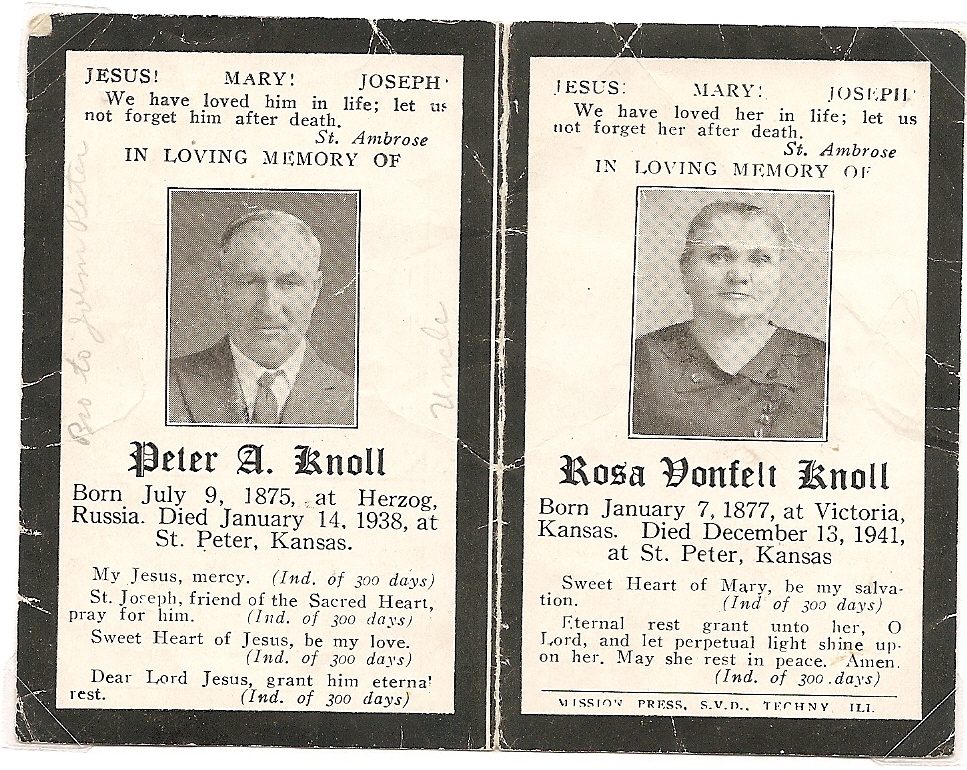

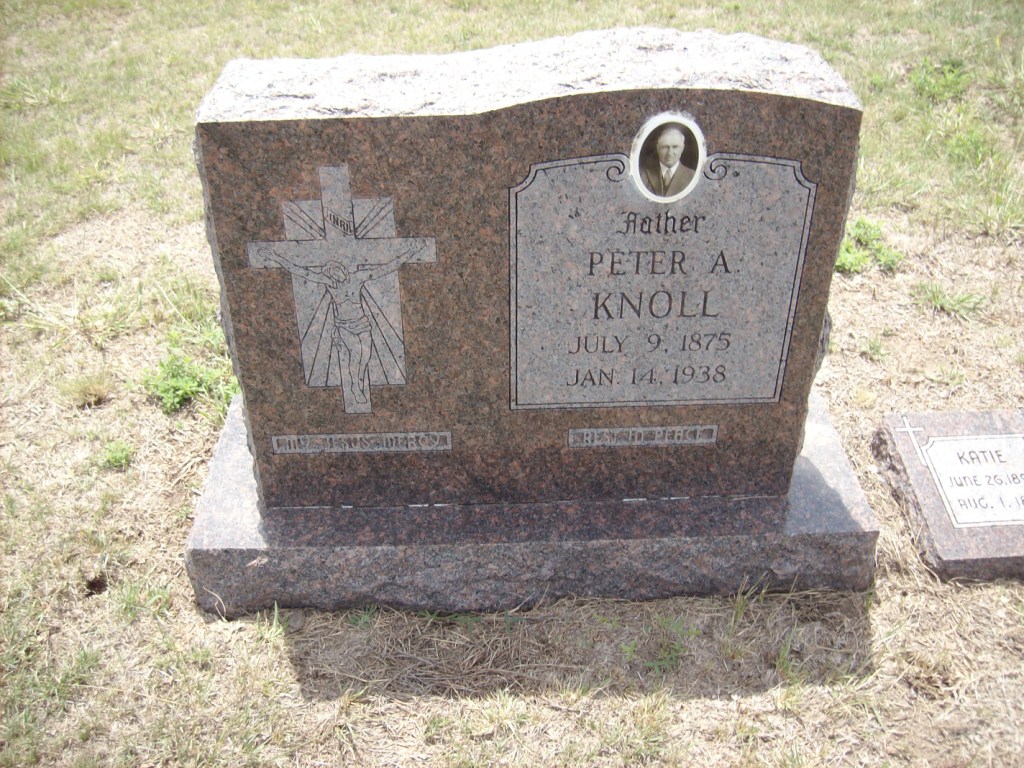

| 8 | Peter A. Knoll, born 9

Jul 1875 in Herzog, Samara, Russia, worked on his father's farm

when he was old enough and went to school when he could be spared,

naturalized in 1882, married Rosa Von Felt 11 Feb 1896 in

Victoria, Ellis, Kansas, lived with parents, wife, and baby son

and worked as a merchant in a general store in Bryant, Graham,

Kansas in 1900, 1905 (occupation not noted), 1910, 1920, 1925, and

1930, appointed postmaster at St. Peter, Graham, Kansas 15 Jan

1907, died 14 Jan 1938 in St. Peter, Graham, Kansas, buried at St.

Anthony Cemetery, Graham county, Kansas. Wife: Rosa Von Felt, b. 7 Jan 1877 in Victoria, Ellis, Kansas to -- Von Feld and Catherine Hoffman, lived in Bryant, Graham, Kansas with son Alex and daughter Margaret in 1940, d. 13 Dec 1941 in St. Peter, Graham, Kansas, bur. St. Anthony Cemetery, Graham county, Kansas. Children: Joseph P. Knoll (m. Anna Brungardt), Alexander Knoll, Adam Knoll (m. Barb --?), Wendelin Knoll (m. Caroline Applehans), Rose Knoll, Mary Knoll, Anna Knoll, Adolph Knoll, and Margaret Knoll. In the 1900 census, Rosa is noted as being the mother of 3 children, 1 living; Peter and Rosa likely had two children other than the ones listed above, who died young. |

| 9 | Four more children.

According to the 1900 census, Katharina was the mother of twelve

children, four of whom were living at the time of the census. This

means that an additional four children are unaccounted for in both

family and primary records. Their names and genders are not known. |

Summary of Sources

- Knoll, Anna, “Adam Knoll and Catherine Pfeifer,” “The Knoll and Pfeifer Families in Russia,” "John Peter Knoll and His Family," biography.

- Author unknown, "John Peter Knoll," biography.

- Hobbs, Gertrude, “St. Peter, Kansas,” excerpts from "History of the St. Peter Community," The Hill City Times, 30 Aug 1979.

- Laing, Francis S., German-Russian Settlements in Ellis County, Kansas, Ellis county, Kansas, 1910, reprinted from Kansas Historical Collections, Vol. XI, Kansas State Historical Society.

- Boyd, Darryl and Dreiling, Trecil (comp.), Rohleder Parish Records 1801 to 1857, https://volgaparishes.com/rohleder_page.html, 2022.

- Copies of St. Fidelis Catholic Church, Victoria, Ellis, Kansas church records from the files of Darryl W. Boyd.

- Copies of St. Fidelis Catholic Church, Victoria, Ellis, Kansas church records from the files of Darryl W. Boyd.

- Leus, Pavel M. (Trans.), Rupp, Kevin D. (Comp.), and Leiker, Anthony (Comp.), Revision List (Census) of the Colony of Herzog, Russia (Susly): A Census of the Village in 1834, Hays, KS, 2002.

- Leus, Pavel M. (trans.), Rupp, Kevin D. (comp.), Herzog, Russia (Susly): A census of the Village in 1850, December 12, 1850, Hays, KS: Kevin D. Rupp, 2002.

- Pflug, Waldemar (trans.), 1857 Census of Herzog (Susly), Russia, translated from FHL 2373592, microfilmed from the original records in the state archives of Samara province.

- Source: Year: 1876; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: M237, 1820-1897; Microfilm Roll: Roll 405; Line: 9; List Number: 704, Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

- Ancestry.com. U.S. and Canada, Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, 1500s-1900s [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc, 2010. Original data: Filby, P. William, ed. Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, 1500s-1900s. Farmington Hills, MI, USA: Gale Research, 2012.

- Dewey, Thomas Emmet (reporter), Reports of Cases Decided in the Courts of Appeals of the State of Kansas, Vol. 7, February Term, 1898, Topeka, KS: J.S. Parks, State Printer, 1899, pages 352-363.

- Ancestry.com. U.S., Appointments of U. S. Postmasters, 1832-1971 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

- Tenth Census of the United States, 1880. (NARA microfilm publication T9, 1,454 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1900. T623, 1854 rolls.

- Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910 (NARA microfilm publication T624, 1,178 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. (NARA microfilm publication T625, 2076 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930. T626, 2,667 rolls.

- United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1940. T627, 4,643 rolls.

- Ancestry.com. Kansas, U.S., State Census Collection, 1855-1925 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com.

- Prayer cards found in a manila envelope formerly in the possession of Florence (Mahler) Boyd.

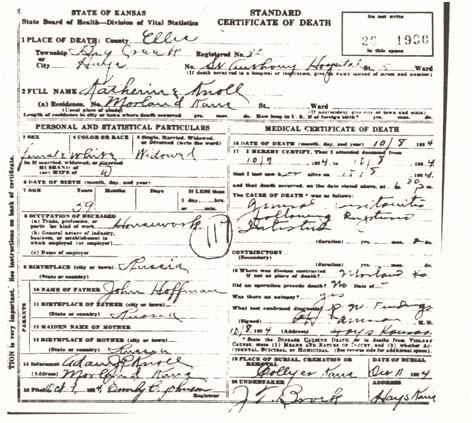

- Photocopies of death certificates of Kathrine (Pfeifer) Knoll, John Peter Knoll, and Katherine (Hoffman) Knoll from the files of Darryl W. Boyd.

- Gravestones of Katrin and Adam Knoll, Mike Knoll, Anna Maria Knoll, Anna Mary Bender Knoll, John Peter and Katherine Knoll, John A. and Christina Knoll, Peter A. Knoll, and Rosa Vonfelt Knoll, Saint Anthony Cemetery, Graham County, Kansas.

- Grave marker of Elisabeth Knoll, Saint Fidelis Cemetery, Victoria, Ellis, Kansas.

- Gravestone of Peter Andrew and Ursula Weigel, Sacred Heart Cemetery, Emmeram, Ellis, Kansas.

Photos

Click each thumbnail below to open a full-size version of the image in a new tab.

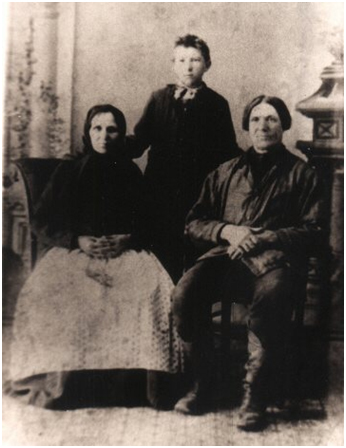

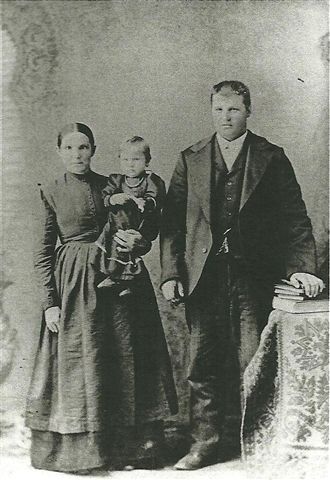

John A., and Adam

Knoll

Knoll

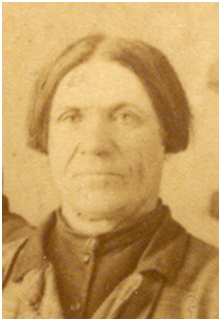

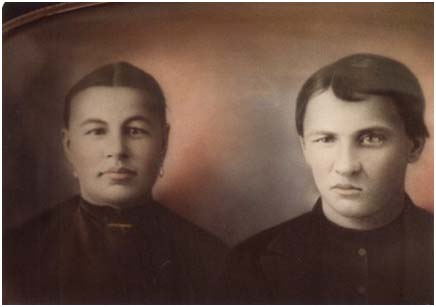

Maria (Riedel) Knoll

Maria (Riedel) Knoll

and child (name not

known)

(Dietz) (Bender)

Knoll

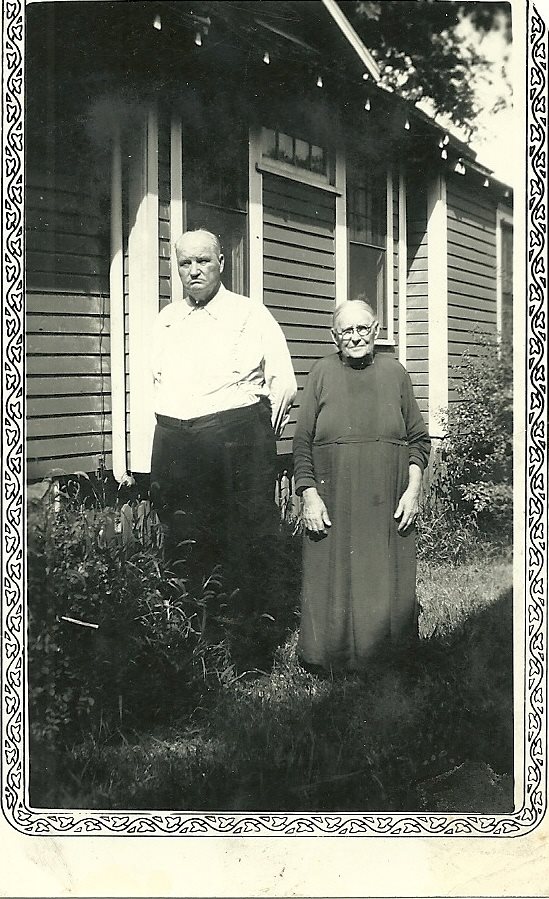

labeled, "Michael

and Anna Knoll" on

Ancestry. Given the

time period in which

it was taken and the

ages of the people in

the photo, Anna is

probably Anna Mary

Dietz.

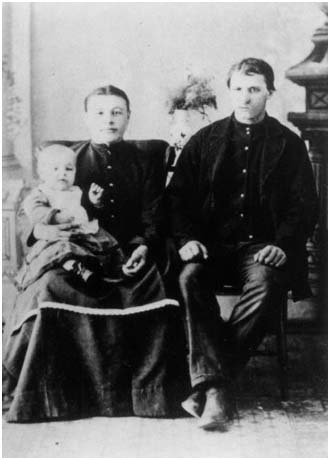

Catherine

(Hoffman) Knoll

and John Peter

Knoll

Elizabeth (Dinkel)

Knoll

(Meier) and John A.

Knoll

(Asselborn) (Schreiner)

Knoll

Photo credit: trecil,

Ancestry.com

Ursula (Geist),

William, Michael,

Barbara, and Peter

Andrew

Knoll

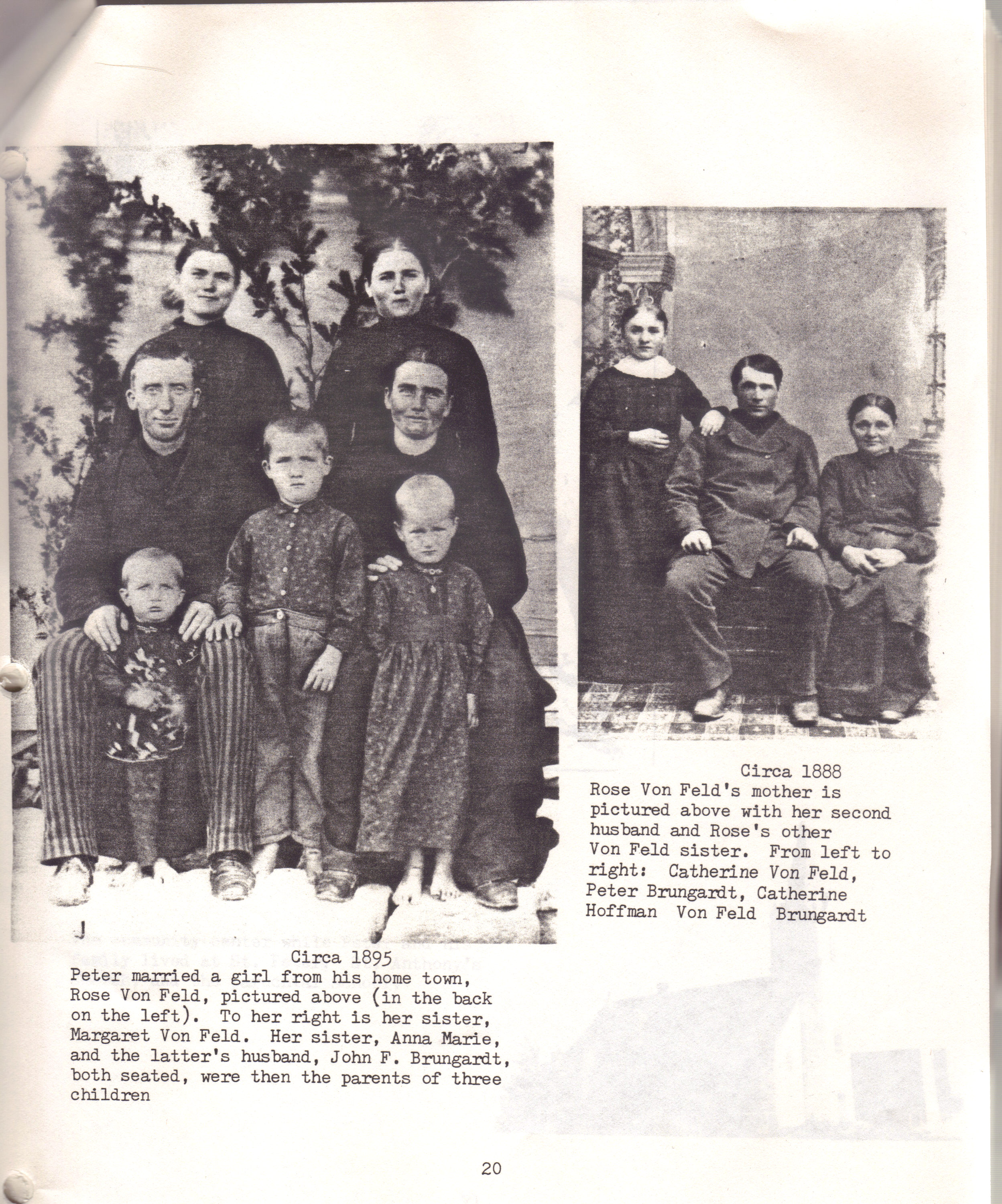

photos (Rosa is in

the photo on the

left, standing in the

back on the left)

Rosa (Von Feld)

Knoll

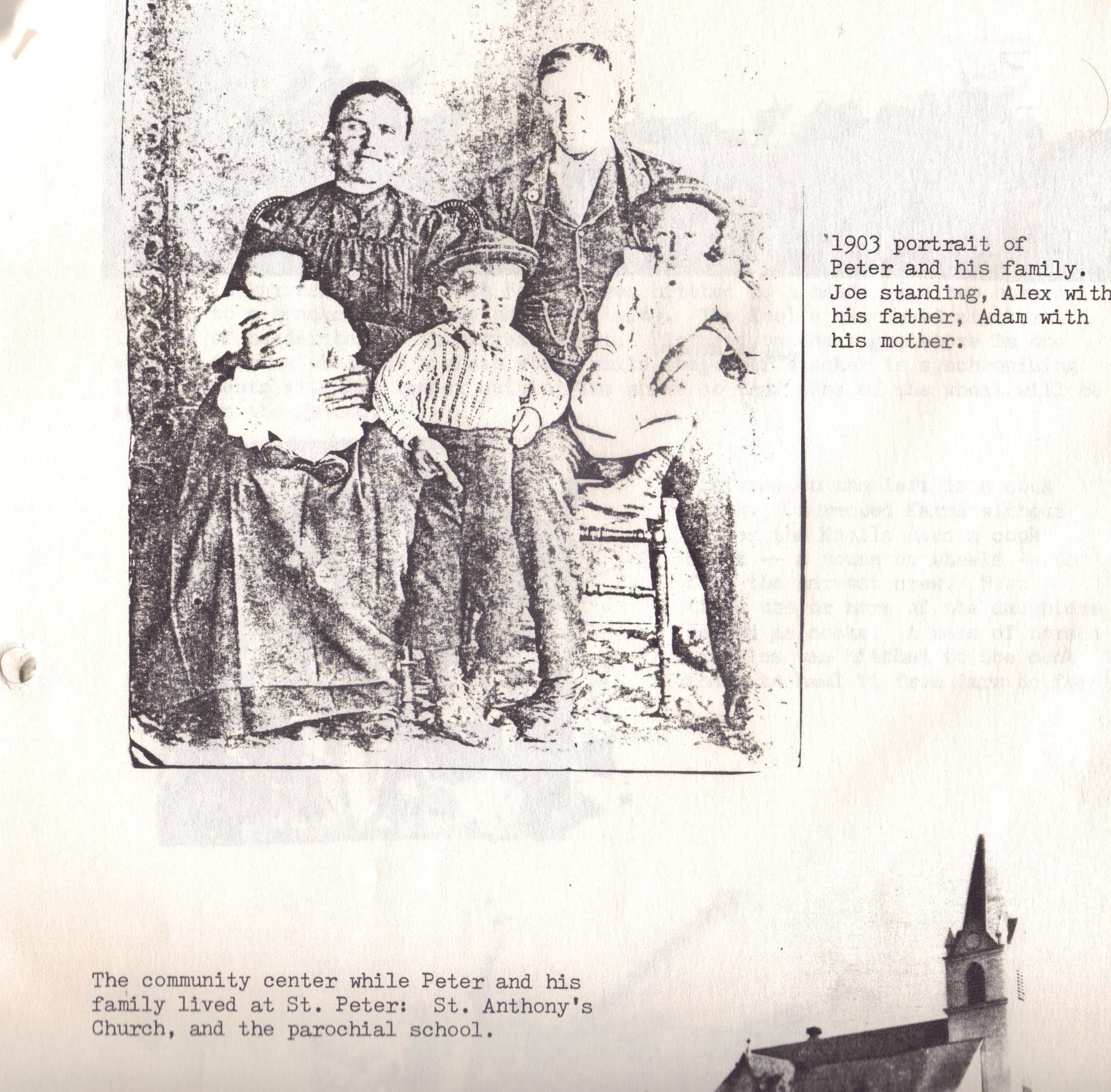

Knoll family, 1903

(children Adam,

Joe, and Alex)

Knoll family, 1928

(sitting: Peter, Rosa,

Margaret

standing: Alex,

Mary, Joseph,

Adolph, Anna,

Rose, Adam)

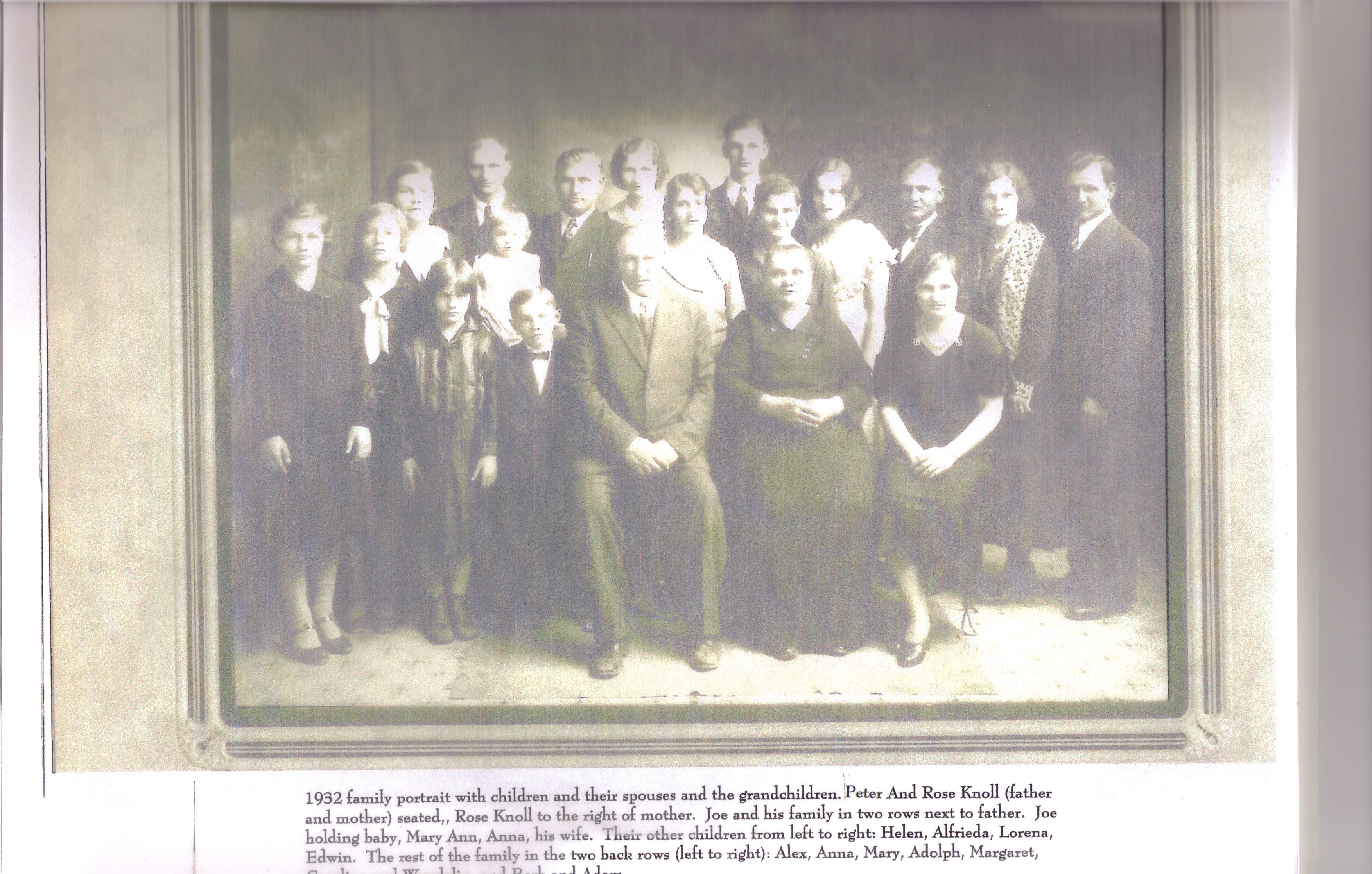

Knoll family, 1932

(bottom line cut off

in the caption:

Caroline and

Wendelin, and Barb

and Adam.)

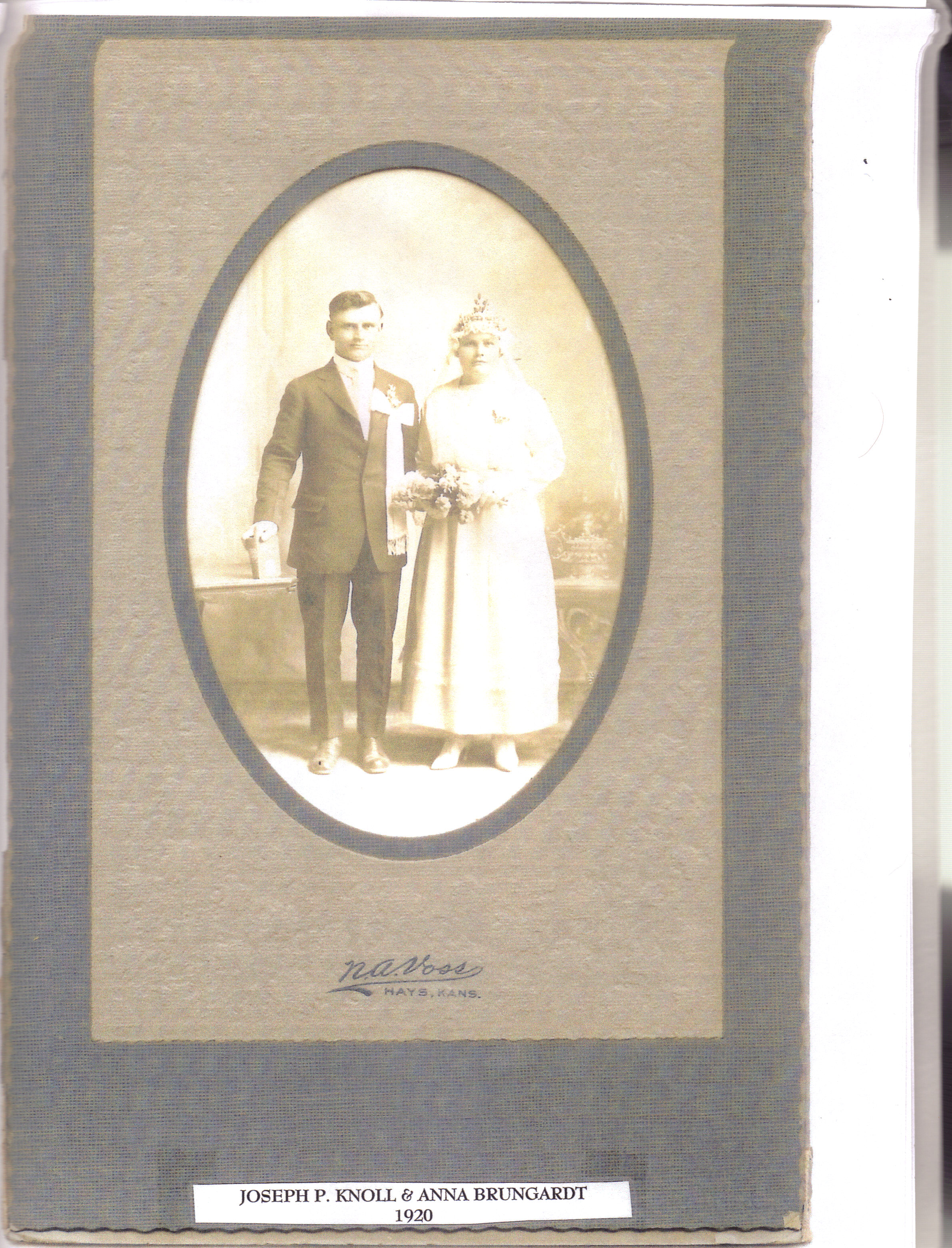

of Peter A. and

Rosa (Von Feld)

Knoll) and Anna

Brungardt

Caroline Applehans

Source Materials

Click on each category below to expand and see the copies of sources used to create the biography above (copyrighted and other restricted items are listed in the summary of sources above but not included below). Click again to close.

ADAM KNOLL AND CATHERINE PFEIFER

by Anna Knoll

Adam Knoll, the son of Johannes Knoll and Margaret Schamberger,* was born in Herzog, Russia on November 11, 1832. His wife, Catherine Pfeifer, the daughter of Adam Pfeifer and Katharine Billinger, was born in Herzog, Russia on November 25, 1834. Their four sons, Michael, John Peter, John, and Peter were also born in Herzog, Russia.

When the family arrived from Herzog, Russia at Victoria on August 3, 1876, Peter was one year old, John was twelve, John Peter was thirteen, and Michael was fifteen.

After their arrival, they did what other settlers did. They proceeded immediately to build a shelter in the village, and within thirteen days, Adam Knoll applied for a homestead, so he would be able to farm as he did in Russia.

On August 16, 1876, Adam Knoll filed homestead application number 344, for a farm northwest of Victoria. The farm was the W1/2, SW1/4 18-13S-16W, and consisted of 71.21 acres. Two weeks later he completed the sod house on his homestead. Five days after that, he established residence on the homestead. He improved the homestead by building a stable on it, digging a well, breaking the sod, and raising crops on the land.

After the family became settled at Victoria, Adam Knoll found employment on the railroad, because he did not make enough money from the homestead to made a satisfactory living. The older sons worked on the homestead, and elsewhere. After Peter was old enough he also helped on the farm, and when he could be spared at home he attended school.

Before Adam Knoll could become the owner of his homestead, he had to become a naturalized citizen, as he did on March 10, 1883. The farm he homesteaded was subsequently patented in his name on November 20, 1883, thus making Adam Knoll the first U.S. citizen to receive title to this tract of land from the U.S. government.

All of Adam Knoll and Catherine Pfeifer's sons married at Victoria. Michael married Anna Marie Riedel in 1878; John Peter married Catherine Hoffman on June 20, 1884; John A. married Elizabeth Dinkel in 1885; and Peter A. married Rose Von Feld on February 11, 1896.

In the summer of 1897, after having lived at Victoria for twenty-one years, Adam Knoll, his wife, their four sons and their families moved to St. Peter, Kansas. Adam Knoll died on November 14, 1901. Catherine Pfeifer died on March 31 1914. Adam Knoll, his wife, and their four sons are buried at St. Peter.

Genealogical information is summarized below about Adam Knoll, his

wife, and their four sons and their spouses.

Name

Born

Died

Adam

Knoll

11-11-1832

married

Catherine

Pfeifer

11-25-1834

1. Michael

Knoll

2-1-1861

married

a) Anna Marie

Riedel

9-8-1862

married

b) Anna Dietz Bender

2. John Peter Knoll

married 6-20-1884

Catherine Hoffman

3. John A. Knoll

married 10-20-1885

a) Elizabeth Dinkel

married 8-26-1895

b) Christine Kessler Meier

married

a) Anna Marie Azelborn Schreiner

married

b) Ursula Giest Weigel

4. Peter A. Knoll

married 2-11-1896

Rose Von Feld

* Further research in records from Russia show that Johannes Knoll

married Elisabetha Jaeckel, not a Margaret Schamberger. There is no

Schamberger family in Herzog or its vicinity, although there was a

Schoenberger family. MB

THE KNOLL AND PFEIFER FAMILIES IN RUSSIA

by Anna Knoll

The Knolls and Pfeifers had ancestral roots in Germany before 1766, and in Russia from about 1766 to 1876. the famous Manifesto (invitation) of 1763 of Catherine the Great, then ruler of Russia, induced these families and many of their compatriots to accept her invitation, and migrate to Russia from their homes in and around Bavaria, Germany. This happened at the end of the Seven Year's War, when the people in Germany were weary of war, and were looking forward to a peaceful way of life.

When these colonists accepted the invitation of Catherine the Great to settle in Russia, they looked forward hopefully to a great future. The promises that induced them to migrate to Russia were free land, exemption from taxation and military service, freedom of religion, and other privileges.

After meeting Catherine the Great in Leningrad, Russia, as the first group did, the colonists' great hopes for the future were dashed when they arrived at their destination. They discovered then that their homes were not what they had been promised, and amounted to nothing more than uninhabited steppes.

About 25,000 colonists, mostly from Germany, were settled in the Volga region, near Saratov, on both sides of the Volga River, from 1764 to 1768. They were settled in 104 agricultural villages with outlying farm land. The Knoll's new home, Herzog, was founded in about 1766 near the Karaman River. It was located on the opposite side of Saratov, about 50 miles from the Volga River.

During their early sojourn in Russia, the Volga German colonists struggled mightily to conquer this frontier with its harsh winter climate, in order to eke out a living and to provide a comfortable home. The colonists encountered many adversities during the early years in Russia because of their poverty, their inadequate housing and farming equipment, and the raids by the Kirghiz on the Volga German villages. Their hardships on this frontier land lasted about 25 years, until around 1790, which was a number of years before Catherine the Great passed away.

The most peaceful time the Knolls enjoyed were probably about the time Johannes Knoll and Margaret (Schamberger) Knoll were born, and extended down through the early married life of Adam Knoll and Catherine (Pfeifer) Knoll. In about 1873, after the Knolls had lived in Russia for about a century, the Volga Germans learned that the Emperor of Russia, Alexander, would repeal the special provision - exemption from military service - that had induced their ancestors to migrate to Russia. Unsettling as this news was to them, they had already been wondering where they might find more land for farming because of the continuing increase in the Volga German population.

The mass exodus from Russia, soon after the repeal of the provision exempting the Volga Germans from military service was most likely triggered more by their need for more land than by Russia's change of policy. At that time they had already heard about the land in the United States that could be purchased from the railroads, and also the land that could be homesteaded.

About three years after the change in policy, on April 8, 1876, when Herzog, Kansas was founded, Adam Knoll, his wife, and their sons were already preparing for the three week journey from Russia to Kansas. Soon after their arrival at Herzog on August 3, 1876, Adam Knoll filed a homestead application, which meant that he had to become a naturalized citizen before he could become the owner of the homestead.

Adam and Catherine Knoll's decision to come to the United States in 1876 was a carefully considered decision. It was based on what happened from 1873 until a Volga German colony was established in Herzog (now Victoria), Kansas on April 8, 1876. Adam Knoll and his wife needed time to make this momentous decision because they were then in the prime of life, and were the parents of four minor children.

The first of the series of events that led to Adam Knoll's search for a new home was the repeal in 1873 of the special privileges that induced his ancestors to migrate from Germany to Russia. This event triggered a meeting at Herzog, Russia, in the spring of 1874, where the search for new homes began to be discussed publicly by the Volga Germans. The outcome of that meeting was that five Catholic scouts were chosen to go to the United States to find out if the land that they had heard about was suitable for Volga German agricultural colonies.

The five scouts, and scouts from other Volga German colonies sailed from Hamburg, Germany on July 1, 1874. Their reports about the United States were favorable enough to induce some Volga German families to form a colonizing expedition the following year, in the fall of 1875. Although the members of this colonizing expedition did not know where they would settle when they left Russia, they eventually founded three Volga German settlements in early 1876. One of those founded was by a group of settlers from Adam Knoll's home town, Herzog, Russia.

Although the settlers from the various Volga German villages that formed this colonizing expedition did not all leave Russia at the same time, they did leave on the same ship from Germany. They took passage in Bremen, Germany, on the steam ship Ohio on November 2, 1875, and after a rough 21 day voyage landed in Baltimore, Maryland.

Although the Volga Germans were on the verge of returning to Russia a number of times after arriving at Topeka, they decided to stay after they were shown prairie land in Ellis and Rush counties in Kansas. They decided to found agricultural colonies in early 1876 in these two counties not only because the land resembled the steppes of Russia, but also because the land was being offered to them at prices they could afford. The three Volga German colonies founded in Kansas in 1876 were Liebenthal, Catherine, and Herzog.

Herzog, Russia (now Victoria, Kansas), the place which later became the home of Adam Knoll and his family was located near the geographical center of the United States adjacent to the Kansas Pacific Railroad. It was half a mile north of Victoria, which was then settled by wealthy Englishmen, most of whom eventually pulled up stakes and left. The Volga German village named Herzog was established on April 8, 1876 by 23 families from Herzog, Russia, who named it after their hometown in Russia.

Soon after Herzog, Kansas was founded, Adam Knoll and many other families from Herzog, Russia prepared to emigrate to this newly formed village.

Adam Knoll and his family and other Volga Germans began their journey to their new home in the United States with a 50 mile wagon trip from Herzog, Russia to the seaport Pokrowsk. They traveled by boat across the might Volga River to Saratov. From there they left by train enroute to Bremen, Germany, traveling through Russia, Poland, and Germany.

After taking passage in Bremen, Germany, on the steamship Mosel, of the North German Lloyd Line, they crossed the Atlantic Ocean, and arrived in the Port of New York on July 29, 1876. From New York they traveled by train to the central part of the United States, and on August 3, 1876, reached their destination.

The families arriving and settling in Herzog, Kansas on August 3, 1876 included Adam Knoll (five family members), and Michael Pfeifer, Sr. (13 family members).

ST. PETER, KANSAS

Excerpts from "History of the St. Peter Community"

by Gertrude Hobbs

The Hill City Times, Aug. 30, 1979

The Volga-Germans people started to migrate to America via Russia in 1875 as escapees from the thickly populated country of Germany. Many were seeking land to farm.

In 1763 and 1767, there were 28,000 Germans were lured to Russia by the lavish promises of Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia. Due to poverty and unemployment, many Germans migrated to Volga Valley in Russia only to find mistreatment, hardships, and Russianized schools. The Volga-Germans boys were drafted into the Russian army. The men and women were shipped to Siberia; however, 175,000 of them froze and starved to death while enroute. Because of these devastating hardships, a scout from the Volga was sent to America to seek better living conditions. They found vast amounts of land to be farmed and also a beckoning by the railroad companies for settlement along their right-away. Hence, the immigration to the U.S. and location in the St. Peter community.

A list of the St. Anthony's Church families around 1909 included Hoffman and Pfeifer families.

In 1894, the first German families came to Bryant Township and concentrated around Hoganville, which was to be moved to the present site of St. Peter in 1900. Mr. Hogan from WaKeeney promised the first settlers a building for their first church and a cemetery site if they would name the settlement "Hoganville." It was located on the John Knoll land, Sec. 15-10-25, which is presently owned by Frank Pfeifer and was about one half-mile west of the present town of St. Peter. In 1895, these few families built a small frame church which satisfied their needs for almost fifteen years. In 1909-10, a new St. Anthony's Church was built. Mr. Alex Schueler of Catherine was both architect and contractor. The new edifice was dedicated in the fall of 1910.

The people were a rather sturdy race of people. However, finance and the German language were handicaps in the English-speaking community.

Cheap land and a few remaining homesteads beckoned many settlers to (St. Peter). A small village of mostly sod houses, a church, and cemetery was started. The first church was a frame house, 20' by 40', purchased at Penokee, and donated by the Close Brothers.

In October of 1898, the site of Hoganville was abandoned and moved to the present site of St. Peter.

Entertainment was provided by having literary in the Banner school building and people rode in lumber wagons to attend. Usually, the mother and father rode in the wagon seat which would provide a slight amount of give when the rough roads were traversed. The children sat in the lumber wagon box on a layer of straw or hay with Grandmother's second-best comforter spread over it. In cold weather, another quilt was placed over their heads as a protection from the weather elements.

The first St. Peter picnic was established in 1902 by Father Charles Weber. These gatherings were continued until the early sixties. Friends and relatives from cities and nearby states would return for these events and visitations with local parishioners. The picnic events were of one-day duration and a huge noon and evening meal consisting of large containers of roast beef, chicken, vegetables, fruit, homegrown cucumbers, pies, and cakes. Tables were set up in the school basement to accommodate the multitude of participants who had come from far and near to enjoy this festive occasion. Games, such as bingo, penny pitch, and dart throw were manned by various parishioners. The day ended with an outdoor pavilion dance.

They came and they built

without a promise;

Not knowing what the future

encumbered;

Now as we look back, their

hearts were in earnest

They left a heritage to be

remembered.

Written by Terry Hobbs

John Peter Knoll and His Family

by Anna Knoll

John Peter Knoll, the second child of Adam Knoll and Catherine Pfeifer, was a prominent farmer at St. Peter, Kansas. Born in Herzog, Russia, on November 12, 1862, he came to the United States with his parents in 1876 at age 13. Because he did not have the opportunity to attend school either in Russia or the United States, he was illiterate. His illiteracy did not prevent him from becoming a prosperous farmer in that he learned to acquire and manage his farms and protect his interests in the school of hard knocks.

On June 20, 1884, John Peter and Catherine Hoffman, the daughter of Johannes Hoffman and Catherine Margaret Bach*, were married in St. Fidelis Church at Victoria. Five of their eight children: Michael, Peter, Anna Barbara, Mike, and Katie, were born at Victoria, and three: Andrew, Adam, and Rosie, were born at St. Peter. Their oldest son, Michael, who died at age five, is buried at Victoria.

When John Peter Knoll and his family moved to St. Peter with his parents and three brothers and their families in 1897, they settled on a farm in section 14-10-25, which is 1/2 mile east of St. Peter. Their house was on a hill on the south side of the road.

After having lived in a sod house six years - from 1897 to 1903, they built a frame house. John Peter and his wife lived in the frame house from 1903 until they died many years later. John Peter died in St. John's Hospital at Salina on September 11, 1920, and his wife, Catherine, died at a Hays hospital October 8, 1924. Both are buried in the cemetery at St. Peter where their son, Andrew, who died in his childhood, is buried.

Besides the place where the family lived, John Peter also became the owner of other land east of St. Peter near his homestead. He bought land in an adjoining section - in section 13-10-25 - and got the 80 acres of land near his home his mother Catherine Pfeifer Knoll owned at the time of her death in 1914. Sometime after she became a widow, his mother moved in with John Peter and his family, and stayed with them until she passed away.

After John Peter and Catherine's three sons, Peter, Mike, and Adam, got married, each of them got some of the land John Peter and his wife owned. Peter, the oldest son, got the farm formerly owned by Catherine (Pfeifer) Knoll. When Peter sold this land in 1929 when he and his family moved to Colorado, Alex Knoll, the writer's brother, bought it. Mike got a quarter in section 13-10-25 after his marriage which his brother, Adam, bought from him in 1939. After the death of John Peter's widow, Catherine, Adam became the owner of the home place - 14-10-25 - and 80 acres in 13-10-25. Adam and his family lived on the home place from the time of his marriage to Agrippina Weigel in December 1923 until he and his family moved to Waukegan, Illinois in 1937. However, Adam continued to own this property from the time of his mother's death until his death in 1966, and he also kept the land he bought from Mike in 1939. Two years after Adam's death in 1966, Adam's wife, Agrippina, gave this land to their two sons, Gilbert and Elmer.

Note: Church records in Russia show that Catherine's mother was Anna Eva Schönberger, not Catherine Margaret Bach. MB

John Peter Knoll

(author unknown)

John Peter Knoll, the second child of Adam Knoll and Katherine Pfeifer, was born in Herzog, Russia on November 12, 1862. He was a prominent farmer at St. Peter, Kansas when he died at St. John's Hospital at Salina, Kansas, on September 11, 1920, at the age of 61 and 10 months.

When he came to the United States with his parents and his brothers in 1876, he helped his father on the homestead north of Victoria, Kansas. Although he was very young (not quite 14), his father needed him to help him with the farming. At that time his oldest brother Michael was working for a rancher at Victoria, Kansas, and his father often worked on the Railroad to support his family and to raise money to help pay the train fare of relatives who wanted to come to the United States from Russia.

On June 20, 1884, he married Catherine Hoffman (she was nearly 17) in St. Fidelis Church at Victoria. Five of their eight children were born at Victoria, Kansas. The oldest son, Michael, who died at age five, is buried at St. Peter. Two other children were born at St. Peter.

After moving to St. Peter when his parents and brothers moved to St. Peter in the summer of 1897, John Peter and his family made their home about one mile east of St. Peter. They lived on a hill on the south side of the road. Their first home was built of sod, and after they became more prosperous, they built a frame house in the village of St. Peter. All of John Peter and Catherine's children, except Rose (the youngest), were married at St. Peter. Rose was married at St. Catherine in Denver, Colorado.

The descendants of John Peter Knoll and Catherine Hoffman live in Kansas, Colorado, Illinois, and Arizona.

German-Russian Settlements in Ellis County, Kansas

The immediate cause of the emigration was the military law of January 13, 1874, which subjected all colonists to military service. Factors in its introduction had been jealousy of the Russian neighbors, owing particularly to the drain in the Crimean war, lack of caution on the part of the colonists, who had been led to sign a document inimical to their liberty. The colonists were averse to military service, because, during the six years, it was almost impossible for Catholic soldiers to fulfill even their Easter duty of receiving the sacraments; only members of the Greek church could rise to an officer's rank; treatment left much to be desired.

In June, 1871, an edict had limited the period of exemption from military service to ten years, with the provision that, as to furnishing recruits, the laws ruling colonists should continue in force only till the publication of a general law on military duty. In this period of ten years colonists might emigrate to other countries without forfeiture of any property. This was not generally known. It was emphasized in a peculiar way during a term of court at Novousensk. Balthasar Brungardt, one of the jurors who had been schreiber (secretary) of Herzog for nine years, and whose attention had been called to the paragraph the colonialostaw (law book) by a mirovoj (secretary), entered into a bet with a Mr. Kraft, who denied the liberty to emigrate, both leaving the decision to the procuror (state's attorney) on the morrow. In the presence of several hundred colonists the procurer affirmed the right of emigrating.

It was largely this occurrence which led to a meeting of about 3000 colonists at Herzog in the spring of 1874. Balthasar Brungardt was one of the speakers. His knowledge of the geographical subject he had drawn from a geography imported from Germany, and from Professor Stelling, who taught history and geography in the seminar (college) at Saratow during Brungardt's college days, 1860-'64, being at the same time official of the comptoir. Stelling was born on the Pacific (his father, a native of Courland, washed gold in California), and delighted to speak of America. In his discourse Mr. Brungardt spoke of Brazil and Nebraska as desirable places for new homes, giving preference to the latter place because colder.

A result of this meeting was the election of five delegates, who, at the expense of their respective communities, were to investigate Nebraska, with a view of settling there...Their report was favorable, and subsequently four of the five emigrated.

Toward the end of December, 1874, two other explorers...were sent on a like mission...They spent about a week in Kansas, and returning to their homes reported unfavorably, thus deterring quite a number from emigrating.

With the five explorers mentioned above went Anton Kaeberlein, of Pfeifer, and others as far as New York. Their destination was Arkansas. On his return, A. Kaeberlein reported that the land pleased him, but not the custom of living on farms instead of living in villages...

The first draft of soldiers in the colonies precipitated matters. On November 24, 1874, four were drafted in Herzog; on December 11 twenty-one were drafted in Katharinenstadt. The formalities required of emigrants were a release from the town authorities on a two-thirds vote of the Gemeinde (made up of the heads of families), from the Kreisamt, and, finally, a pass from the governor.

...

The largest single expedition was that which set out shortly after Mr. B. Brungardt had undertaken to secure passes for 108 families at eighteen rubles; after some delays, and some gifts to the governor, all were secured but four; these latter were refused because the persons had drawn red ballots and were held for recruits. A petition to the war department and one to the minister of war were fruitless. As a last resort a telegram was sent to the czar and arrangements made to delay the answer so that it would reach the colony only after all had passed the Russian border. The whole party occupied seventeen coaches on leaving Saratow, June 26/July 8. At Duenaburg they were joined by a party of Mennonites, who occupied ten coaches. The larger body separated at Eydtkuhnen. Some of the first arrivals had complained in letters of treatment on board the ship of the North-German Lloyd, and had advised their friends who contemplated emigration to take another route. Because of this Mr. Weinberg, as agent of the Hamburg-American line, prevailed on some to go by Hamburg; this route was taken by those who settled in Munjor, Schoenchen, and Liebenthal. The others arranged for transportation to New York at thirty-eight rubles, with an agent of Johanning & Behmer of the North-German Lloyd, and to the number of 1454 souls took passage on the "Mosel." In Castle Garden various offers of transportation were made ranging from $18 to 22. These were refused, and finally an agreement made for sixteen rubles (the ruble had then a rating of seventy-two cents) per passenger. The Mennonites went to Nebraska. The others were Peter Braun, Peter Andrew Braun (3), Andrew Brungardt, sr. (8), Balthasar Brungardt (5), Franz Brungardt, sr. (8), Franz Brungardt (2), John Peter Brungardt, Peter Brungardt (6), Peter Brungardt (9), Alois Dening (8), Michael Dening (6), Andrew Dinkel, George Dinkel (4), John Peter Dinkel (5), Michael Dreiling, sr. (3), Anton M. Dreiling (5), Franz M. Dreiling (4), Michael M. Dreiling (4), Peter M. Dreiling (3), John Dreiling, Elizabeth Dreiling, Paulina Dreiling, John Frank, Joseph Kapp, Adam Knoll (5), Michael Kuhn, sr. (4), John Kuhn, sr. (3), Andrew Kuhn (4), John Kuhn (3), Michael Kuhn (10), Michael Kuhn, jr. (3), Anton Mermis (6), Michael Pfeifer, sr. (13), Adam Riedel (11), Martin Riedel (5), Michael Riedel (3), Peter Rome (3), Ignaz Sander (7), Frederic Schamber (5), Andrew Scheck, sr. (3), Andrew Scheck (8), Michael Schmidtberger, John Vonfeld (14), John Wasinger (7), John Windholz, Michael Weigel (10), John Wittmann (8), Peter Wittmann (3), Martin Yunker (8), Peter Yunker (4), all of Herzog, Russia; John Leiker (7), Anton Rupp (8), Caspar Rupp (6), Jacob Rupp (4) of Obermonjour, Russia; Joseph Graf, sr. (5), Martin Quint (8), Michael Quint (8) of Louis, Russia; Henry Gerber of Graf, Russia. All these, excepting Peter Yunker, who remained in Topeka till 1877, made their home in Herzog, arriving in Victoria, August 3, 1876.

Source: Laing, Francis S., German-Russian Settlements in Ellis County, Kansas, Ellis county, Kansas, 1910, reprinted from Kansas Historical Collections, Vol. XI, Kansas State Historical Society. Available at Google Books.

Note: "Name lists are arranged alphabetically; the number in () designates the number of members in the family; at times these numbers include several families, in which case they formed one household; absence of a number denotes that the persons were single. Some Christian names are Englished."

Note: Bolding added by me. MB

Rohleder Parish Records 1801 to 1857

Births and Baptisms

Line: 80

Birth date: 21 Oct 1832

Baptism date: 22 Oct 1832

Child: Johann Adam

Father: Knoll Johannes

Mother: Jegel Elisabetha

Village: Herzog

Witnesses: Johannes Adam Sander & Elisabeth Kuhn

Line: 90

Birth date: 24 Nov 1832

Baptism date: 25 Nov 1832

Child: Catharina

Father: Pfeifer Johnn Adam

Mother: Billinger Catharina

Village: Herzog

Witnesses: Peter Riedel & Catharina Weigel

Line: 174

Birth date: 2 Dec 1854

Baptism date: 3 Dec 1854

Child: Elisabetha

Father: Knoll Johannes Adam

Mother: Pfeifer Catherina

Village: Herzog

Witnesses: Michael Pfeifer & Elisabeth (wife of Peter) Schönberger

Line: 150

Birth date: 17 Oct 1856

Baptism date: 18 Oct 1856

Child: Johannes Andreas

Father: Knoll Johannes Adam

Mother: Pfeifer Catherina

Village: Herzog

Witnesses: Andreas Brungardt, Anna Maria Billinger

Marriages

Line: 21

Date: 28 Oct 1852

Groom: Knoll Johannes Adam

Age: 26

Marital Status: S

Village: Herzog

Bride: Pfeifer Katharina

Age: 18

Marital Status: S

Village: Herzog

Groom's parents: Johannes Knoll & Elisabetha Jaeckel

Bride's parents: Adam Pfeifer & Katharina Billinger

Where married: Herzog

Witness: Peter Schoenberger

Deaths

Line: 42

Date: 25 Jun 1855

Age: 6 mo

Name of deceased: Knoll Elisabetha

Village: Herzog

Cause: fever

Parents: Adam Knoll and Katharina Pfeifer

Line: 108

Date: 9 Dec 1857

Age: 1

Name of deceased: Knoll Johannes Andreas

Village: Herzog

Cause: fever

Parents: Johannes Adam Knoll and Katharina Pfeifer

Source: Boyd, Darryl and Dreiling, Trecil (comp.), Rohleder Parish Records 1801 to 1857, https://volgaparishes.com/rohleder_page.html, 2022.

Images of church records are shown below as thumbnails. Click on each of the thumbnails to view a larger version of the records in another tab.

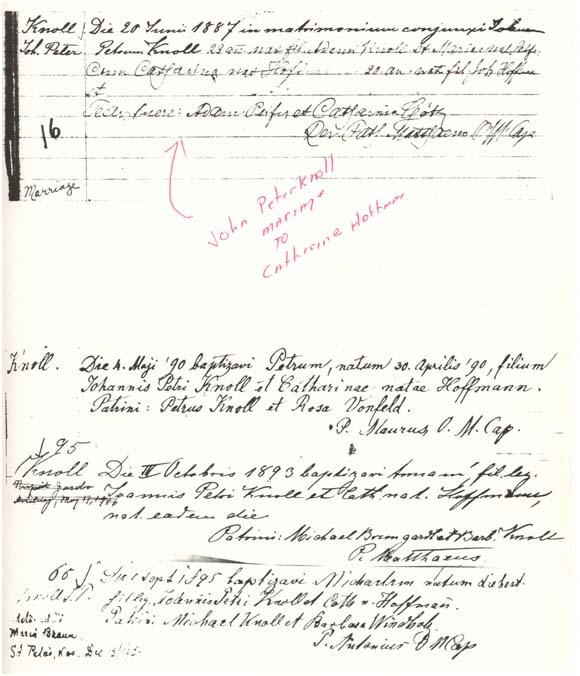

St. Fidelis Catholic Church, Victoria, Kansas

Johann Petrus Knoll

and Catharina

Hoffman,

20 Jun 1887

Baptisms,

Petrus, Anna,

and Michael Knoll

Source: Copies of St. Fidelis Catholic Church, Victoria, Ellis, Kansas church records from the files of Darryl W. Boyd.

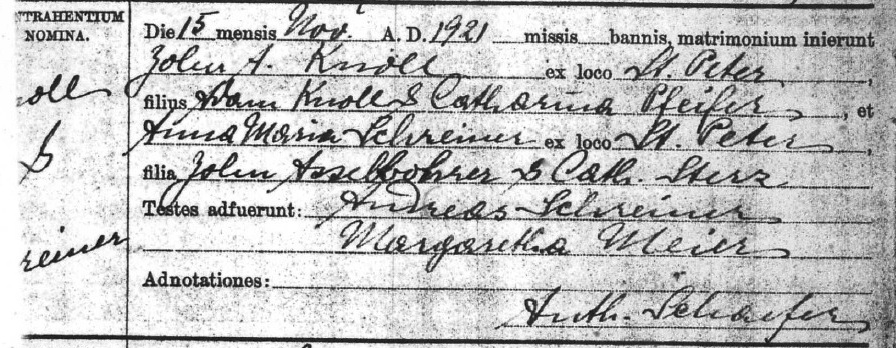

Church records from St. Peter, Kansas

John A. Knoll

and Anna Maria

(Asselborhn) Schreiner,

15 Nov 1921

Anna Maria (Asselborn)

(Schreiner) Knoll,

26 Jul 1935

Source: Copies of church records from St. Peter, Graham, Kansas church records, uploaded to Ancestry by user trecil, 2020.

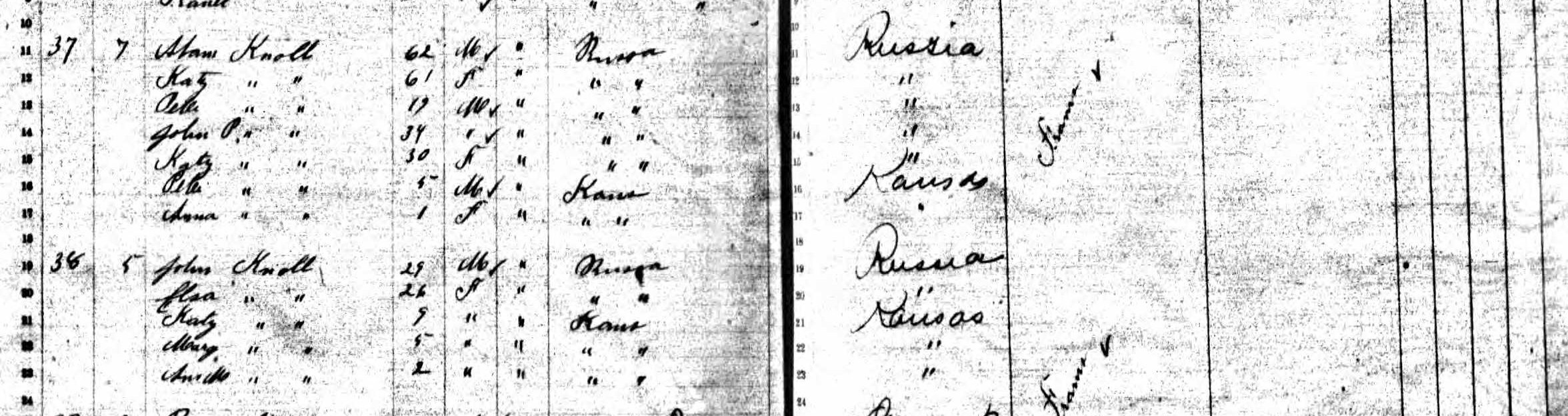

Herzog Census, 12 Dec 1834

Name: Johannes Knoll

Birth:

1806 Herzog (Susly), Russia

Spouse: Elisabeth ?

Birth: 1809

Children

1 M Johannes Knoll

Birth: 1827

2 M Johann-Adam Knoll

Birth: 1832

3 M Michael Knoll

Birth: 1833

4 F Teresa Knoll

Birth: 1828

5 F Elisabeth Knoll

Birth: 1830

Name: Adam Pfeiffer

Birth: 1800

Father: Pfeifer

Mother: ?

Spouse: Katharine

Birth: 1806

Children

1 M Johannes Pfeiffer

Birth: 1826

2 M Michael Pfeiffer

Birth: 1828

3 F Maria Eva Pfeiffer

Birth: 1821

4 F Anna Maria Pfeiffer

Birth: 1823

5 F Magdalena Pfeiffer

Birth: 1830

6 F Katharine Pfeiffer

Birth: 1832

Source: Leus, Pavel M. (Trans.), Rupp, Kevin D. (Comp.), and Leiker, Anthony (Comp.), Revision List (Census) of the Colony of Herzog, Russia (Susly): A Census of the Village in 1834, Hays, KS, 2002.

Herzog Census, 30 Jul 1850

Name: Johannes Knoll

Birth: 1806

Father: Franz Knoll (1763-1827)

Mother: Elisabeth (1768- )

Spouse: Elisabeth

Birth: 1808

Children

1 M Johannes Knoll

Birth:

1827 Herzog (Susly), Russia

Spouse: Sabina ?

2 F Elisabeth Knoll

Birth:

1830 Herzog (Susly), Russia

3 M Johann Adam Knoll

Birth:

1832 Herzog (Susly), Russia

4 M Michael Knoll

Birth:

1833 Herzog (Susly), Russia

Death:

1844 Herzog (Susly), Russia

5 M Franz Knoll

Birth:

1837 Herzog (Susly), Russia

6 M Johann Peter Knoll

Birth:

1841 Herzog (Susly), Russia

7 F Katharine Knoll

Birth:

1846 Herzog (Susly), Russia

Name: Adam Pfeiffer

Birth:

1800 Herzog (Susly), Russia

Spouse: Katharine ?

Birth: 1807

Children

1 M Johannes Pfeiffer

Birth:

1826 Herzog (Susly), Russia

Spouse: Margaret ?

2 M Michael Pfeiffer

Birth:

1828 Herzog (Susly), Russia

Spouse: Teresa ?

3 M Andreas Pfeiffer

Note: No age was given for this child in the 1850 census.

4 F Katharine Pfeiffer

Birth:

1833 Herzog (Susly), Russia

5 F Barbara Pfeiffer

Birth:

1836 Herzog (Susly), Russia

6 F Anna Maria Pfeiffer

Birth:

1841 Herzog (Susly), Russia

7 F Katharine Pfeiffer

Birth:

1846 Herzog (Susly), Russia

Source: Leus, Pavel M. (trans.), Rupp, Kevin D. (comp.), Herzog, Russia (Susly): A census of the Village in 1850, December 12, 1850, Hays, KS: Kevin D. Rupp, 2002.

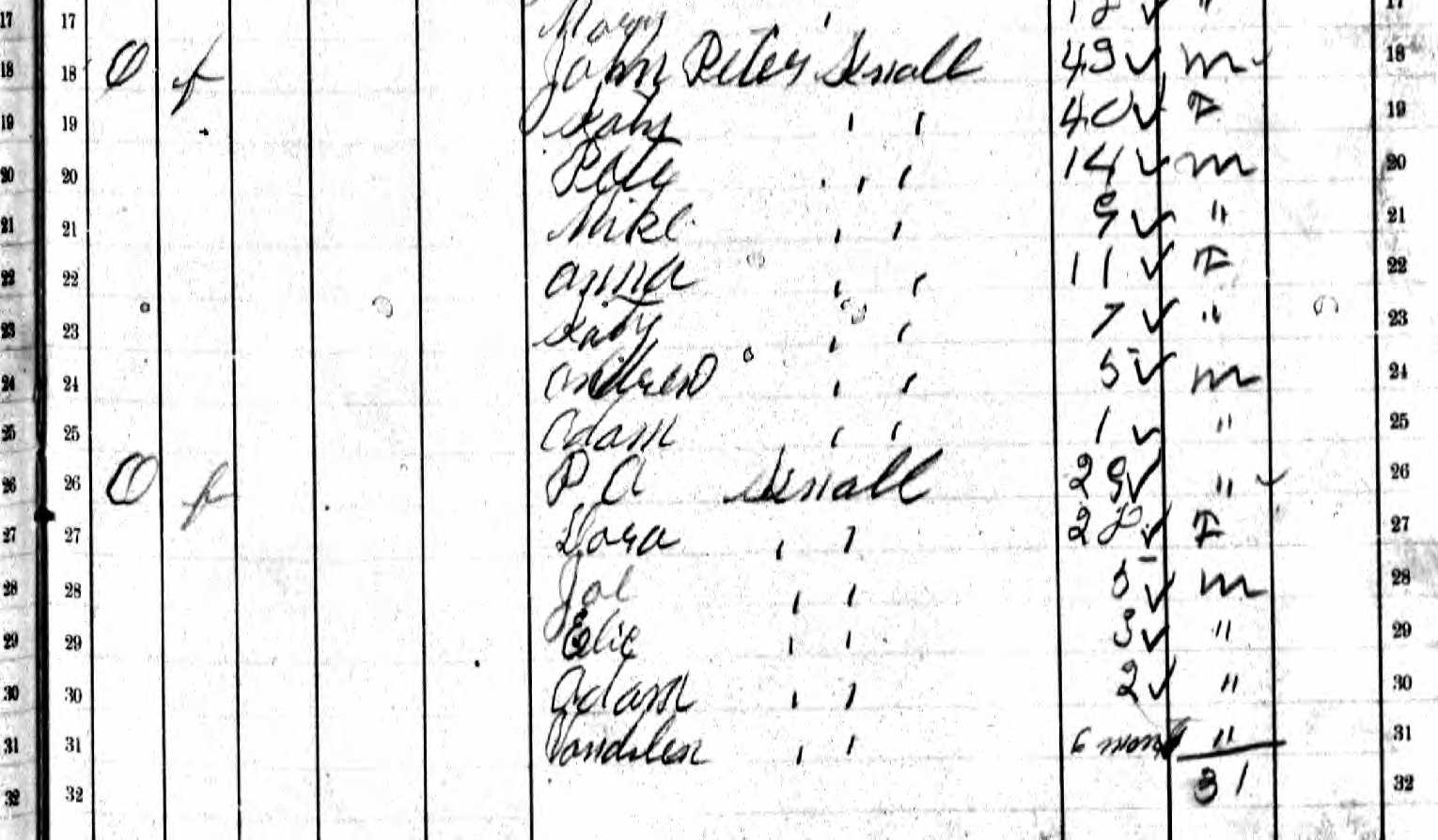

Census, 4 Nov 1857

Household number: 98 (119)

Age in 1850 Age in 1857 Notes

Johannes

Knoll

head

44

51

Elisabetha

Eckel

spouse

48

"Geckel"

Johannes

son

23

1/2

31

Sabina

Schönberger

daughter-in-law

28

Johann

Adam

grandson

7

Johannes

grandson

4

Johann

Adam

son

18

25

Katharina

Pfeifer

daughter-in-law

25

"Peifer"

Andreas

grandson

1

Franz

son

13

20

Anna Katharina

Hergert

daughter-in-law

19

Johann

Peter

son

9

16

Katharina

daughter

4

11

Anna

Katharina

daughter

7

Source: Pflug, Waldemar (trans.), 1857 Census of Herzog (Susly),

Russia, translated from FHL 2373592, microfilmed from the

original records in the state archives of Samara province.

Images of immigration records are shown below as thumbnails. Click on each thumbnail to view a larger version of the record in another tab.

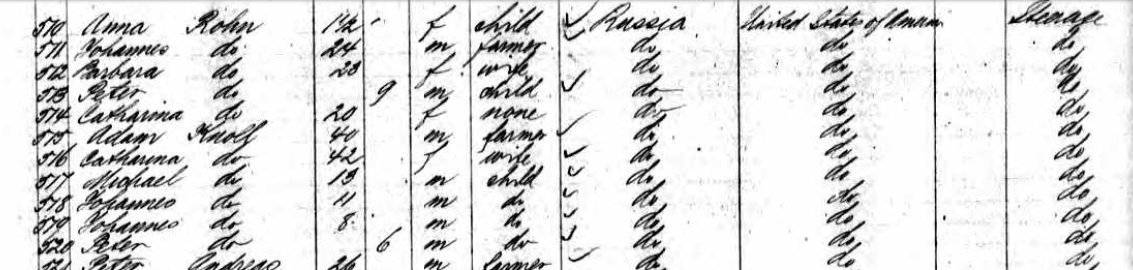

Passenger List for the Mosel, sailing from Bremen to New York, arriving 29 Jul 1876

Source: Year: 1876; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: M237, 1820-1897; Microfilm Roll: Roll 405; Line: 9; List Number: 704, Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

U.S. and Canada Passenger and Immigration Lists Index

Name: Adam Knoll

Arrival

Year:

1876

Arrival

Place:

Kansas

Source Publication

Code: 4497

Primary

Immigrant:

Knoll, Adam

Annotation: Lists of

immigrants from places in Russia to America (Baltimore then to

Kansas), 1875-1878, pp. 493-502. Reprinted as a separate pamphlet

(1910?, 40p.). The 1876 arrivals are also listed in no. 4019, Knoll.

See also no. 1682, Dreiling.

Source Bibliography: LAING, REV.

FRANCIS B. "German-Russian Settlements in Ellis County, Kansas." In

Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, 1909-1910, vol.

11. Topeka, Kansas: State Printing Office, 1910, pp. 489-528.

Page:

497

Source: Ancestry.com. U.S. and Canada, Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, 1500s-1900s [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc, 2010. Original data: Filby, P. William, ed. Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, 1500s-1900s. Farmington Hills, MI, USA: Gale Research, 2012.

The First National Bank of Russell v. John Peter Knoll et al.

No. 126

1. Pleading and Practice—Defect of

Parties—Demurrer. A demurrer on account of a “defect of parties”

plaintiff is given by law for a defect and not for an excess or

misjoinder of parties. A misjoinder of parties plaintiff is not

reached by a demurrer. The petition states a cause of action—but one

cause of action; therefore the demurrer was properly overruled.

2. —Demurrer Properly Overruled, When. The demurrer

to the evidence was properly overruled for the reason that the

evidence fairly tended to prove all the allegations of the petition

and made a prima facie case.

3. —Instructions Refused—Estoppel—Homestead.

Instructions requested by plaintiff in error examined, and held, that

the court properly refused to give the instructions asked, for the

reason (1) that such instructions were not applicable to the facts in

the case; (2) that there is no such rule of estoppel as contended for;

(3) that the homestead comprises a part of the lands mentioned; the

instruction is inapplicable to such portion, and was therefore

properly refused.

4. —Motion to Strike Out—Immaterial Evidence. The

motion of plaintiff in error to strike out evidence should have been

sustained; the evidence was immaterial; it could not in any manner

affect the substantial interests of either party to the case. The

refusal to strike out the same by the trial court does not constitute

such error as to require a reversal of the case.

5. —Exceptions Unavailable—Inquiry Immaterial.

Exceptions will not be available to a party where both plaintiff and

defendant participate in the introduction of evidence concerning a

controversy which is wholly foreign to the triable issues in the case,

and where the whole scope of such inquiry is immaterial and therefore

cannot affect the substantial rights of either party.

6. — —Failure to Designate Portion of Record.

Exceptions to the refusal of the court to sustain an objection to

evidence, or to strike out improper evidence, will not be considered

by this court where the party objecting fails to designate and point

out the portion of the record in which such evidence and exceptions

can be found.

7. —Evidence Examined, Held Sufficient. The evidence

examined and found to very satisfactorily establish that Knoll and his

mortgagees are the owners and entitled to the possession of the

property in controversy.

Error from Ellis district court; Lee Monroe, judge. Opinion filed

March 4, 1898. Affirmed.

A. J. Bryant, and H. G. Laing, for plaintiff in error.

David Rathbone and Reeder & Reeder for defendants in error.

The opinion of the court was delivered by

McElroy, J.: This action in replevin was commenced by John Peter Knoll

to recover the possession of certain wheat and grain in stack on the

farm of Adam Knoll, the father of John Peter. Thereafter, before

answer day, Alexander Phillip and Tena Knoche, as mortgagees of John

Peter Knoll, were made parties, and the plaintiffs filed an amended

petition alleging that John Peter Knoll was the owner of the property

and entitled to the immediate possession thereof; that the defendant

T. K. Hamilton, as sheriff, unlawfully seized and unlawfully detains

the possession of the property from John Peter Knoll; that Tena Knoche

and Alexander Phillip have a special ownership in the property that

Tena Knoche has a mortgage upon the property, which is set out

verbatim; that Alexander Phillip has a mortgage upon the property, and

his mortgage is likewise set out; and that the ownership of the

plaintifls and their right to the possession of the property is

inseparably connected. The case was subsequently dismissed as to

Alexander Phillip, and the action proceeded in the names of John Peter

Knoll and Tena Knoche as plaintiffs.

The defendant Hamilton, as sheriff, filed a demurrer to the petition,

upon the following grounds: (1) A misjoinder of parties plaintiff; (2)

a misjoinder of causes of action; and (3) that the petition did not

state facts sufficient to constitute a cause of action. This demurrer

was by the court overruled and exceptions thereto saved, and the

defendant Hamilton filed an answer consisting of a general denial.

Subsequently, on his application, the First National Bank of Russell

was substituted, with its consent, under the provisions of section 45

of the code, as defendant in the action. The bank thereupon filed an

answer as substituted defendant: (1) A general denial; (2) alleging

that since the commencement of the suit it had bought the note given

by John Peter Knoll to Alexander Phillip, which was secured by the

mortgage set out in the petition, and alleging that it was the owner

and holder of the note and mortgage and of all the rights of the

mortgagee, Phillip, thereunder; and further alleging that, at the time

of the commencement of the action, the lien under that mortgage was

prior and superior to the interests of the plaintiffs in the property;

denying that the plaintiffs or either of them had any right, title or

interest in the property or any part thereof; denying that either of

them, at the commencement of the suit, was entitled to the possession

of the property or any part thereof; and denying that the bank was

wrongfully detaining the property from the plaintiffs, or either of

them; (3) alleging that it paid the note held by Alexander Phillip and

secured by the mortgage set out in the plaintiffs’ petition, and that

by reason of such payment it is entitled to subrogation to the rights

of Alexander Phillip under the mortgage.

To the second and third defenses the plaintiffs demurred, (1) for the

reason that neither of them stated facts sufficient to constitute a

defense; (2) that the second and third grounds of defense in the

answer did not state facts sufficient to entitle the defendant to the

relief it prayed for in its answer; (3) that the defendant, since the

commencement of the action, had commenced another action upon the note

described in its answer, and that that action was then pending in the

same court upon an appeal from a justice of the peace. This demurrer

was by the court overruled.

Thereupon the plaintiffs filed a reply, in which they alleged (1) the

commencement of the action upon the note in the justice's court

referred to in their demurrer; (2) a general denial. To this reply the

defendant bank demurred that the first count of the reply did not

state facts sufficient to constitute a defense to the matters set up

in the answer. This demurrer was overruled, the defendant excepting.

The plaintiffs then dismissed this action as to a part of the property

described in their petition. The case came on to be tried at the

February term, 1896, and the defendant demanded a separate trial as to

each of the plaintiffs, John Peter Knoll and Tena Knoche, which was

denied by the court. The case was tried to a jury, and the verdict and

special findings were for the plaintiffs, upon which judgment was

rendered in the alternative for a return of the property, or its value

in case return could not be had. It appeared that the defendant

Hamilton, as sheriff, had retained the property, and sold the same

under his writ at the suit of the plaintiff in error. There are

seventeen assignments of error, So far as necessary we shall notice

them in their order.

The first assignment of error is based upon the overruling of the

demurrer of the defendant Hamilton to the plaintiffs’ amended

petition. The first ground of demurrer is not within the statute. The

statute provides for a demurrer in case of a defect of parties, but

not for amisjoinder of parties plaintiff. (McKee v. Eaton, 26 Kan.

226.) The petition states a cause of action against the defendant

Hamilton, as sheriff. The second ground of the demurrer could not be

sustained by the court for the reason that but one cause of action was

stated. The plaintiffs allege that the defendant Hamilton, as sheriff,

had interfered with the possession of the property of John Peter

Knoll; had seized and unlawfully detained it. It is true the petition

says that the plaintiff Tena Knoche had an interest in the property as

mortgagee of John Peter Knoll, and that Alexander Phillip, as

mortgagee of John Peter Knoll, had an interest in the property adverse

to the sheriff, Hamilton, by virtue of his mortgage. There was but one

cause of action stated, and that was for the recovery of the

possession of the property so wrongfully taken and withheld by the

sheriff. Neither of these mortgagees were necessary parties to the

action. However, it might be proper to say in this connection, that

there was nothing improper in the joinder of the mortgagees with the

mortgagor for the purpose of recovering the property in which they

were all interested as against the adverse claim of the sheriff. The

supreme court of the United States, in the case of Geekie v. Kirby

Carpenter Co., 106 U. S. 389, which arose in the state of Wisconsin,

says:

“Klass having the general property in the logs, and Geekie a special

property in them, and the logs having been taken by the defendant from

the possession of Geekie, who held them as sheriff, under the

attachment against Klass, it was proper for both to join in the suit.

The damages found to have been sustained by each may be added together

and awarded to them as plaintiffs. The damages to Klass are the value

of the logs…The damages to Geekie are the…expenses.”

It is true that was an action for conversion. Under the decisions of

our own supreme court, a petition for conversion must allege a right

of possession and the wrongful taking and conversion by the defendant,

practically the same as in replevin. The code of Wisconsin upon the

question of parties is not materially different from our own. Section

35 of our code says:

“All persons having an interest in the subject of the action and in

obtaining the relief demanded may be joined as plaintiffs, except as

provided otherwise in this article.”

The owner of the property and his mortgagees have an interest in the

mortgaged property. They have a community of interest as against a

trespasser, and they have an interest in this case in obtaining the

relief demanded; that is, a return of the possession of the property

to the rightful owner, that their mortgage interests might be

protected thereby against an adverse claimant. If the property could

not be recovered in specie under the alternative money judgment, the

respective interests of the mortgagor and mortgagee could be protected

by the court. The provisions of the code are entitled to a liberal

construction in protecting the rights of litigants. The plaintiff in

error would be in no manner prejudiced by the fact that the mortgagees

were parties plaintiff in the suit. Their presence could not deprive

it of any defense or of any right, or impose upon it any additional

burden. The demurrer was properly overruled. This ruling does not in

any manner conflict with the cases decided by the supreme court cited

by counsel in their brief. Upon this same contention counsel rest

their right to a separate trial as against each of the plaintiffs.

There was but one issue to try: Who had the right to the possession of

the property at the time the suit was begun?

The third assignment of error is that the judgment should have been

for the defendant bank upon the pleadings. It is based upon the same

theory, and must fall with the first contention, unless it may be said

that the plaintiff in error, by the acquisition of the Phillip note

and mortgage after the commencement of the suit, could justify the

seizure of the property. The Phillip mortgage was purchased and

assigned long after the taking and detention of the property by the

sheriff, long after this action was begun. The plaintiff in error was

substituted for the sheriff, and the bank could urge any defense which

might be rightfully urged by the sheriff. By the terms of the mortgage

John Peter Knoll was entitled to the possession of the property, and

nothing appeared in the facts of the case to controvert this right.

The answer does not allege any default on the part of the mortgagor,

by reason of which the mortgagee or his assignee would be entitled to

take the property under the mortgage.

The fourth assignment of error is that the demurrer to the evidence

should have been sustained for the reason that the Alexander Phillip

mortgage, which had been assigned by him to the bank, did not contain

any provision for John Peter Knoll retaining possession of the

property, and that the bank, as the assignee of the mortgage, had the

sole right to the property. As we have heretofore said, this mortgage

to Alexander Phillip by John Peter Knoll clearly expressed by its

provisions that John Peter Knoll should retain possession until the

happening of some contingency therein expressed. There was no

allegation nor was there any evidence offered to show that either of

the contingencies provided for in the mortgage had occurred. And

further, the question to be tried was, Whose property was it? Was the

sheriff's seizure rightful? Did the sheriff have a right to seize and

hold possession of the property under his writ; and if not. did the

bank have a right to insist upon the possession of the property under

some other claim of title? The demurrer to the evidence was properly

overruled.

The fifth assignment of error is based upon the fact that the court

permitted Harry Knoche, the husband of Tena Knoche, to remain with her

in the courtroom during the trial, notwithstanding he was a witness in

her behalf or in behalf of John Peter Knoll. In the exclusion of

witnesses from the court-room during the progress of the trial the

court had a discretion, and it cannot be said that it abused its

discretion in this instance.

The sixth assignment of error is that the court refused the request of

the plaintiff in error to instruct the jury that the assignment of the

note by Alexander Phillip to the bank carried with it the mortgage.

This is a sound proposition of law. The evidence of the debt carries

with it the security. But it had no application to the facts in this

case, and was an immaterial matter.

The seventh assignment of error is that the court refused to give as

law the eighth request of the plaintiff in error. It appears that at

the sale of the property in controversy by the sheriff under his writ

of execution against Adam Knoll, Michael Knoll, a son of Adam and a

brother of John Peter, attended the sale and bid in a part of the

property—several stacks of wheat. He had the wheat thrashed and

subsequently sold a part of it to his brother, John Peter, for seed to

sow the land. By the eighth request referred to in this assignment,

counsel for the plaintiff in error asked the court to say to the jury

that, by purchasing this wheat from his brother Michael, John Peter

Knoll had elected to ratify the sale and was estopped from asserting

his right to the possession. There is no such rule of estoppel known

to us, and our attention has not been directed to any authority to

sustain this contention.

The eighth assignment of error is based upon the court's refusal to

instruct the jury:

“If you believe from the evidence that Adam Knoll transferred to John

Peter Knoll the use of all his land, in consideration of $100 a year

and future support of Adam Knoll and wife, and, at the time of making

such transfer and agreement, Adam Knoll and John Peter Knoll knew that

Adam Knoll was largely indebted to the First National Bank of Russell,

and that Adam Knoll had no other property out of which the same could

be paid, then such transfer or lease is void as to the defendant

bank.”

Adam Knoll owned the land upon which this wheat was grown. It

comprised 300 acres, which included the homestead of himself, his

wife, and his family. And even if it were a sound legal proposition

when applied to land not a homestead, it could have no application

here, as the homestead is here included; and a homestead is something

to which a creditor may never turn for the satisfaction of his debt.

The instruction as requested was properly refused.

The ninth assignment of error is that the court sustained an objection

to a question propounded by the plaintiff in error to Michal Knoll as

to how many stacks he, Michael Knoll, had upon a certain section. The

inquiry was immaterial and the objection was properly sustained. It

mattered not how many stacks of wheat Michael Knoll had on any

section.

The tenth assignment of error is that the court denied a motion of the

plaintiff in error to strike out a part of the testimony of Michael

Knoll. Counsel for plaintiffs were endeavoring to ascertain from the

witness what his source of knowledge was as to the ownership of

certain horses, a matter entirely outside of the issues in the case,

and it was developed finally, that he knew nothing as to the ownership

of the horses except what his brother, John Peter Knoll, had told him.

The motion was to strike out the last answer of the witness. It was an

immaterial matter. It could not in any manner affect the case in the

interest of either party. While it might very properly have been

stricken out, the refusal does not constitute such error as to require

a reversal of the case.

The twelfth assignment of error is that the court overruled an

objection of the plaintiff in error to the testimony of John Schlyer

as to the custom of Russians in giving their children property when

they left home. The record discloses the fact that both parties

entered into this controversy. Both parties introduced evidence pro

and con as to what the custom of Russians was and is in dealing with

their children when they arrive at majority. The plaintiff in error is

in no condition to urge this objection. The whole scope of this

inquiry was immaterial, and could not affect the rights of either

party.

The thirteenth assignment of error is based upon the court's action in

sustaining an objection to a question upon cross examination of Adam

Knoll. We are not referred to the page of the record, or in what

connection this question was asked. We do not find it in the record.

We cannot say from what is set out that the court abused its

discretion in limiting this cross-examination.

The fourteenth assignment of error is so indefinite that we cannot

determine what merit, if any, there is in the contention.

The fifteenth assignment of error is based upon the action of the

court in sustaining an objection to a question asked by the plaintiff

in error of John Peter Knoll. There is no reference to the record in

this connection, and we are not able to say that the action of the

court was erroneous or prejudicial to the rights of the plaintiff in

error.

The sixteenth assignment of error is as follows: “An erroneous

conclusion of the jury in the sixteenth finding of fact, as follows.”

Then is recited an interrogatory submitted to the jury by the court,

and the answer thereto. The interrogatory should not have been

submitted to the jury. It was immaterial. It referred to a transaction

independent of the question of the ownership of the wheat. It referred

to a transfer of property from Adam Knoll to John Peter Knoll, other

than the property involved in the litigation. It is not necessary for

us to examine or determine, therefore, whether the jury reached an

erroneous conclusion or not.

The seventeenth assignment of error is that the verdict is contrary to

the evidence. The evidence is very satisfactory and convincing that

the wheat sought to be recovered by John Peter Knoll and his mortgagee

was honestly his property—was a crop raised by him. There was nothing

in connection with the transactions between father and son in any

manner affecting the title to the property in litigation, of which the

plaintiff in error had any right to complain.

Whether other transactions between the father and son were legitimate,

is immaterial in the determination of this controversy. The title or

right of possession to such other property was not in controversy in

the case at bar.

The evidence sustained the verdict of the jury, and the judgment is

affirmed.

Source: Dewey, Thomas Emmet (reporter), Reports of Cases Decided

in the Courts of Appeals of the State of Kansas, Vol. 7, February

Term, 1898, Topeka, KS: J.S. Parks, State Printer, 1899, pages

352-363. (Available on Google Books; also available in The Pacific

Reporter, March 3-May 19, 1898, St. Paul: West Publishing Co., 1898,

pages 619-623, at Google Books.)

Copies of occupational records are shown below as thumbnails. Click on each thumbnail to view a larger version of the record in another tab.

Appointments of U. S. Postmasters, 1832-1971

Post Office Location:

Saint Peter, Graham,

Kansas

Appointment Date:

15 Jan 1907

Volume #: 85

Volume Year Range:

1893-1930

Source: Ancestry.com. U.S., Appointments of U. S. Postmasters, 1832-1971 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

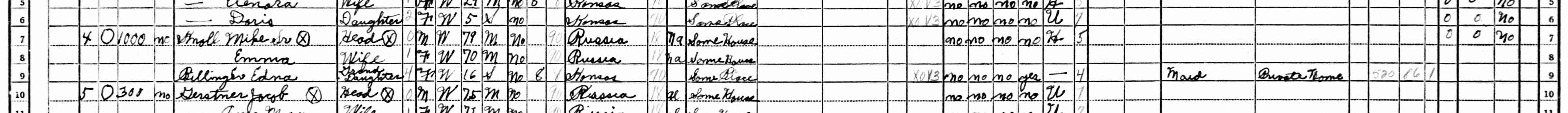

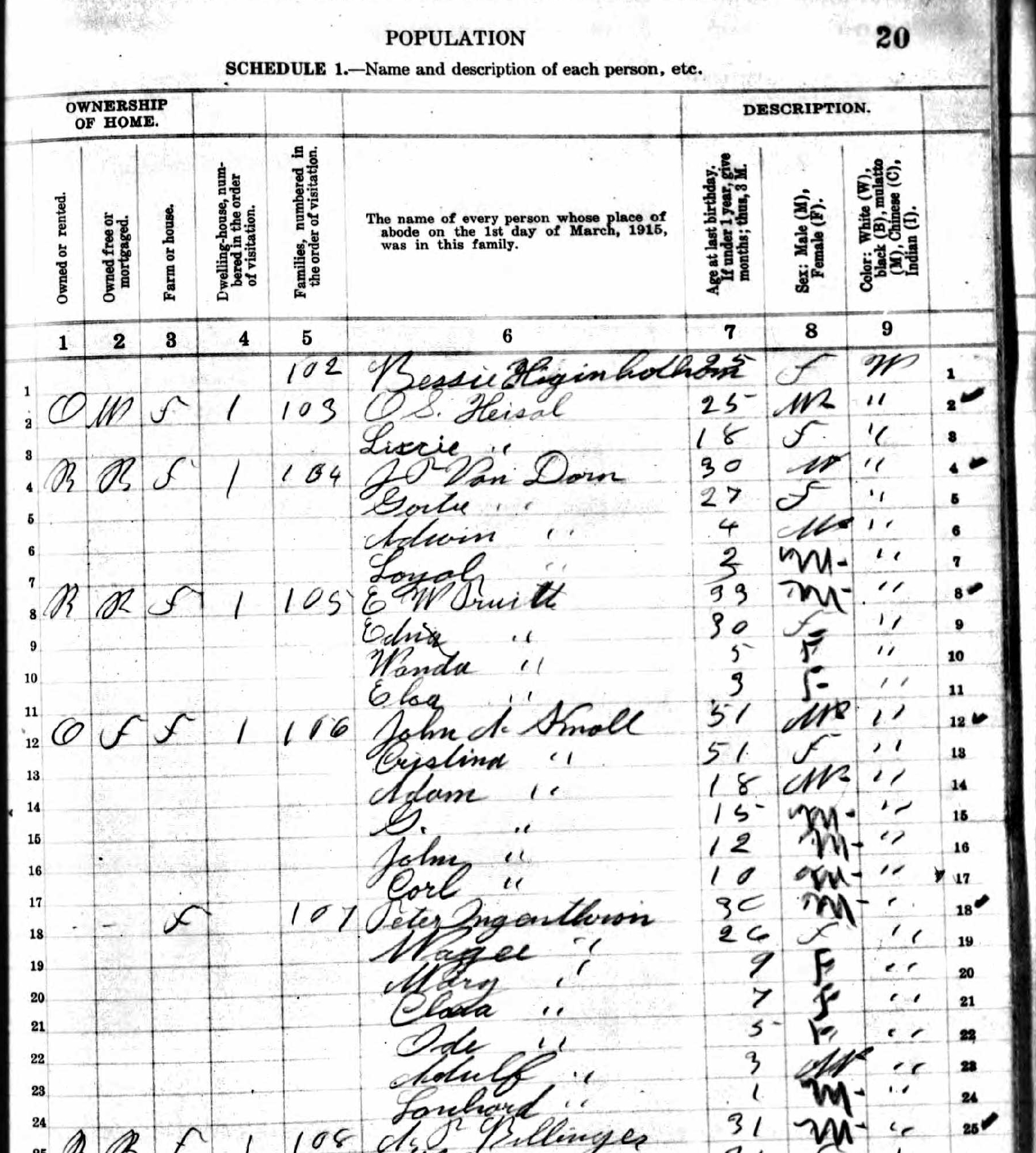

Copies of census records are shown below as thumbnails. Click on each thumbnail to view a larger version of the record in another tab.

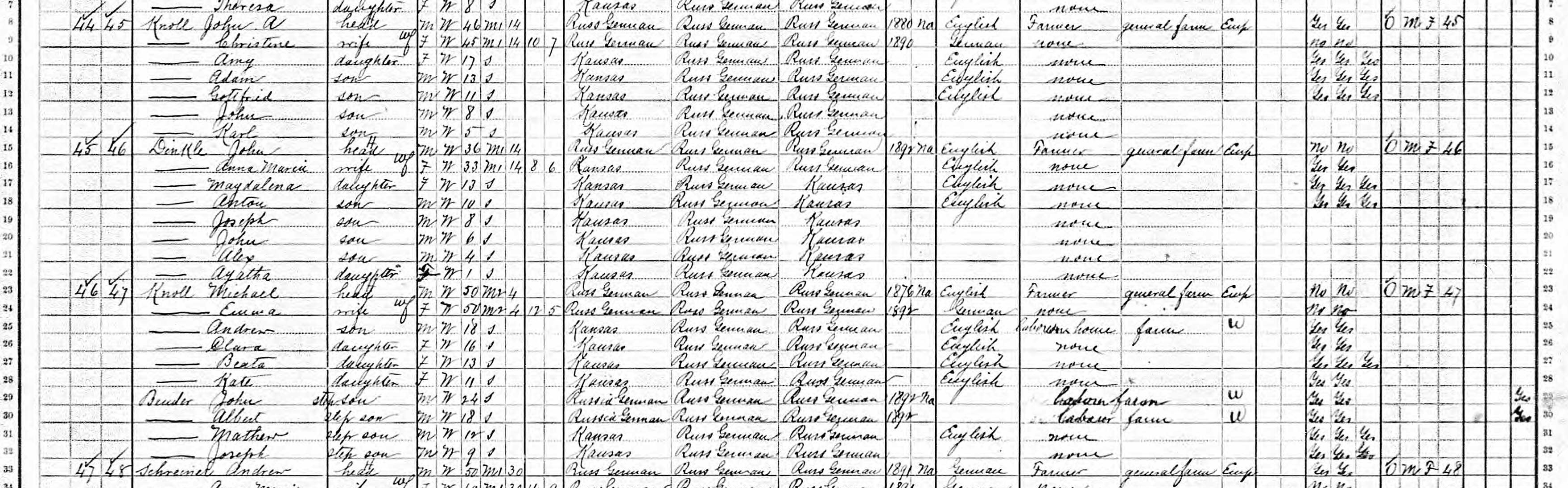

1880

Herzog Township (Hartsook), Ellis, Kansas

Year: 1880;

Census Place: Hartsook,

Ellis, Kansas;

Roll: 381;

Page: 433C;

Enumeration District: 089;

Description: Herzog and

Catherine Townships

Knoll, continued

Year: 1880;

Census Place: Victoria,

Ellis, Kansas;

Roll: 381;

Page: 426B;

Enumeration District: 088

Source: Tenth Census of the United States, 1880. (NARA microfilm publication T9, 1,454 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

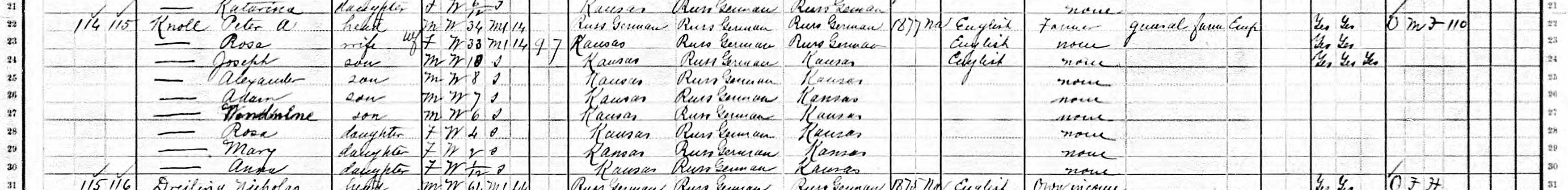

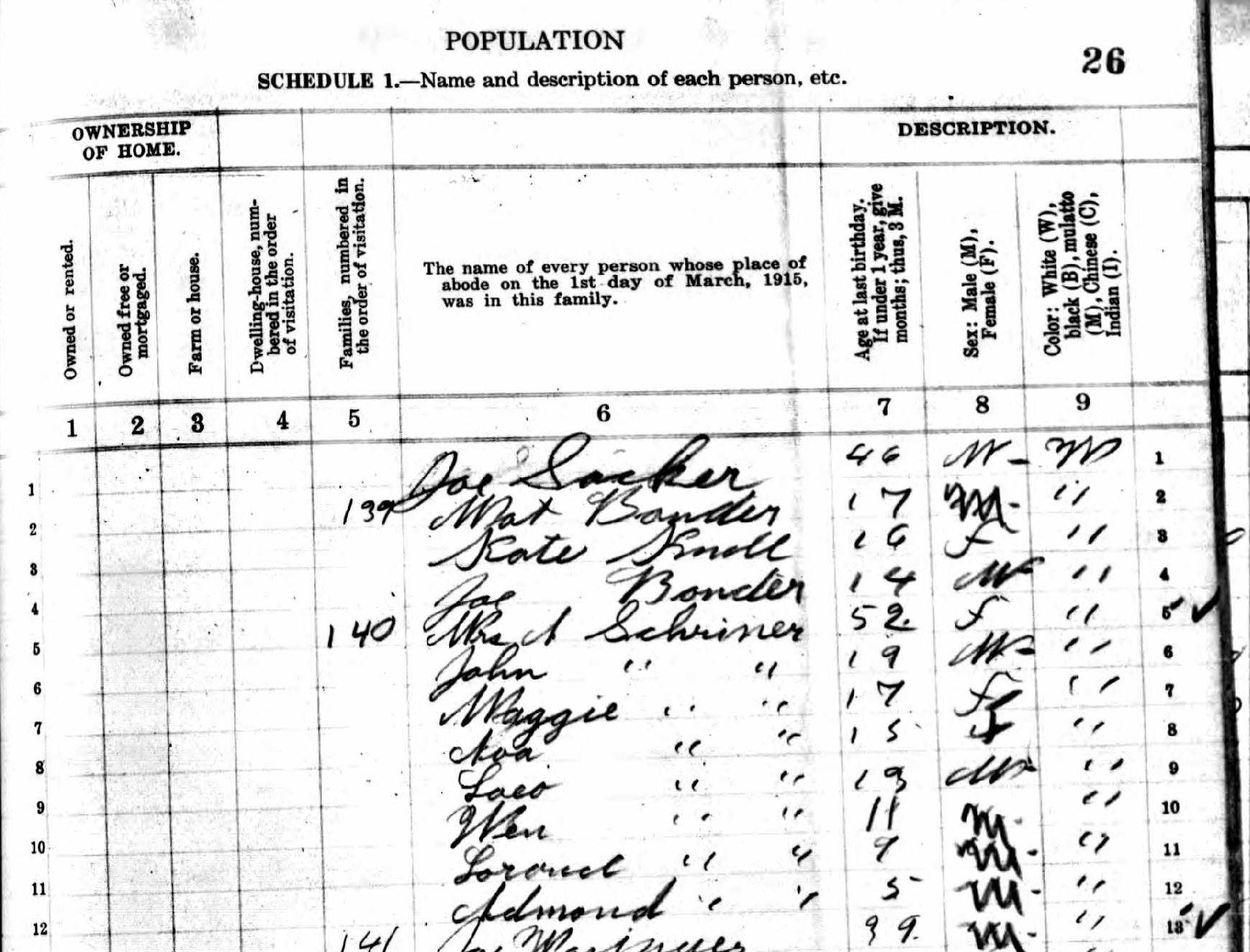

1900

Bryant, Graham, Kansas

Adam Knoll;

Year: 1900;

Census Place: Bryant,

Graham, Kansas;

Page: 6;

Enumeration District: 0036;

FHL microfilm: 1240481

Year: 1900;

Census Place: Bryant,

Graham, Kansas;

Page: 8;

Enumeration District: 0036;

FHL microfilm: 1240481

Knoll, continued

Year: 1900;

Census Place: Bryant,

Graham, Kansas;

Page: 6;

Enumeration District: 0036;

FHL microfilm: 1240481

Knoll, continued

Herzog, Ellis, Kansas

Year: 1900;

Census Place: Hertzog,

Ellis, Kansas;

Page: 7;

Enumeration District: 0020;

FHL microfilm: 1240480

Source: United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1900. T623, 1854 rolls.

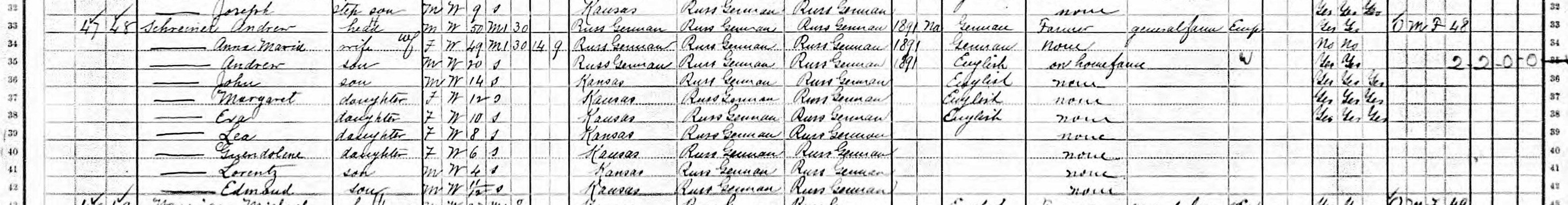

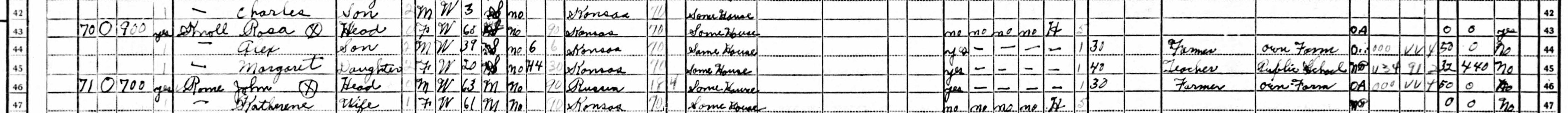

1910

Bryant, Graham, Kansas

Year: 1910;

Census Place: Bryant,

Graham, Kansas;

Roll: T624_440;

Page: 5A;

Enumeration District: 0044;

FHL microfilm: 1374453

Michael Knoll;

Year: 1910;

Census Place: Bryant,

Graham, Kansas;

Roll: T624_440;

Page: 4A;

Enumeration District: 0044;

FHL microfilm: 1374453

Year: 1910;

Census Place: Bryant,

Graham, Kansas;

Roll: T624_440;

Page: 8A;

Enumeration District: 0044;

FHL microfilm: 1374453

Year: 1910;

Census Place: Bryant,

Graham, Kansas;

Roll: T624_440;

Page: 4A;

Enumeration District: 0044;

FHL microfilm: 1374453

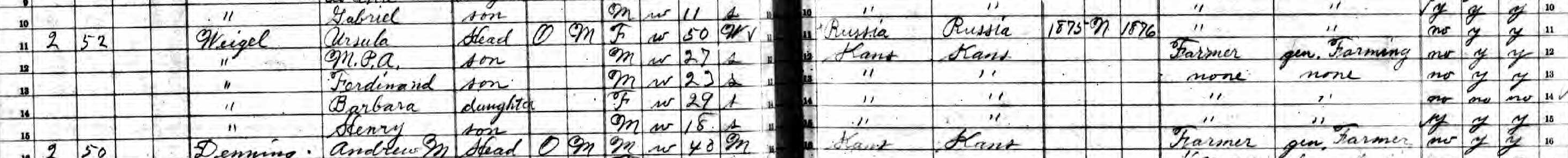

Herzog, Ellis, Kansas

Year: 1910;

Census Place: Herzog,

Ellis, Kansas;

Roll: T624_438;

Page: 10A;

Enumeration District: 0025;

FHL microfilm: 1374451

Source: Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910 (NARA microfilm publication T624, 1,178 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

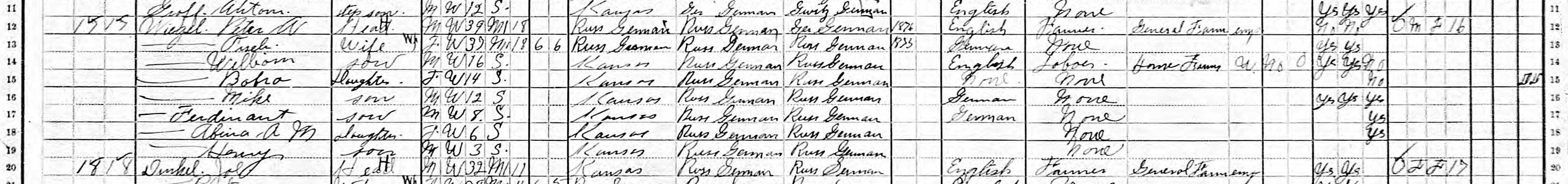

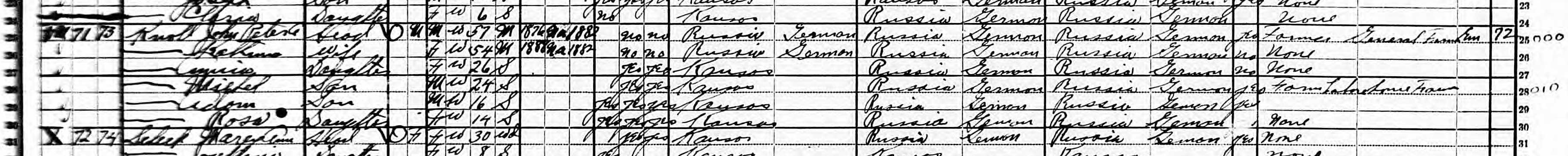

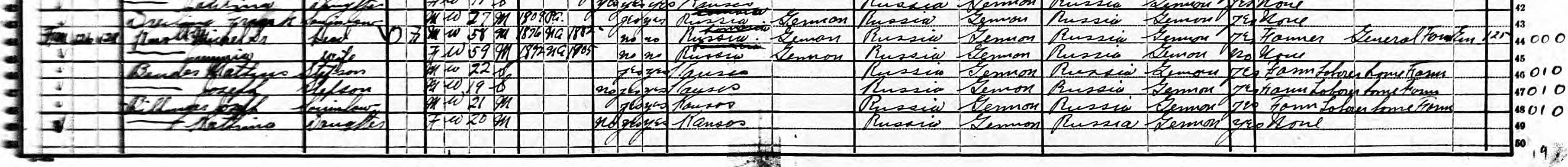

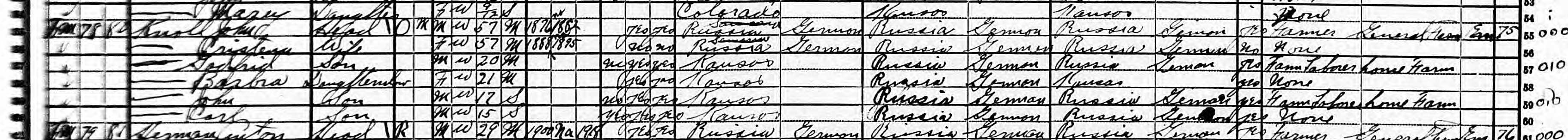

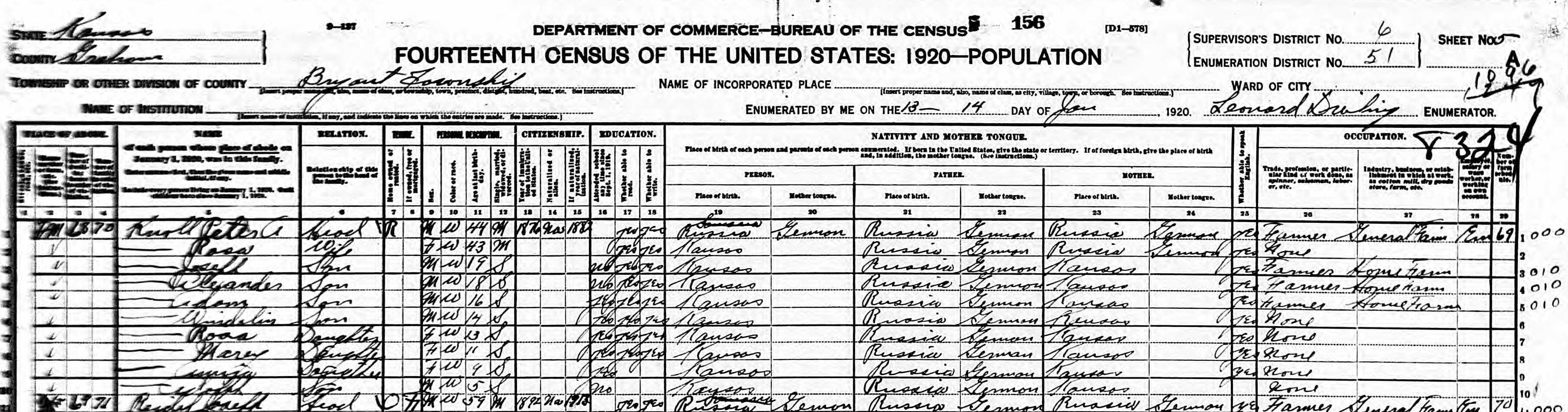

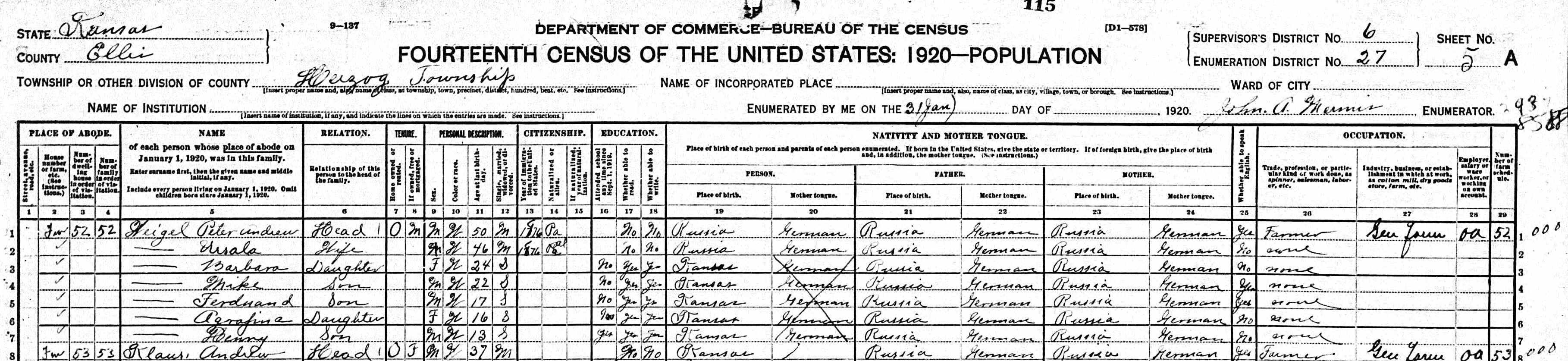

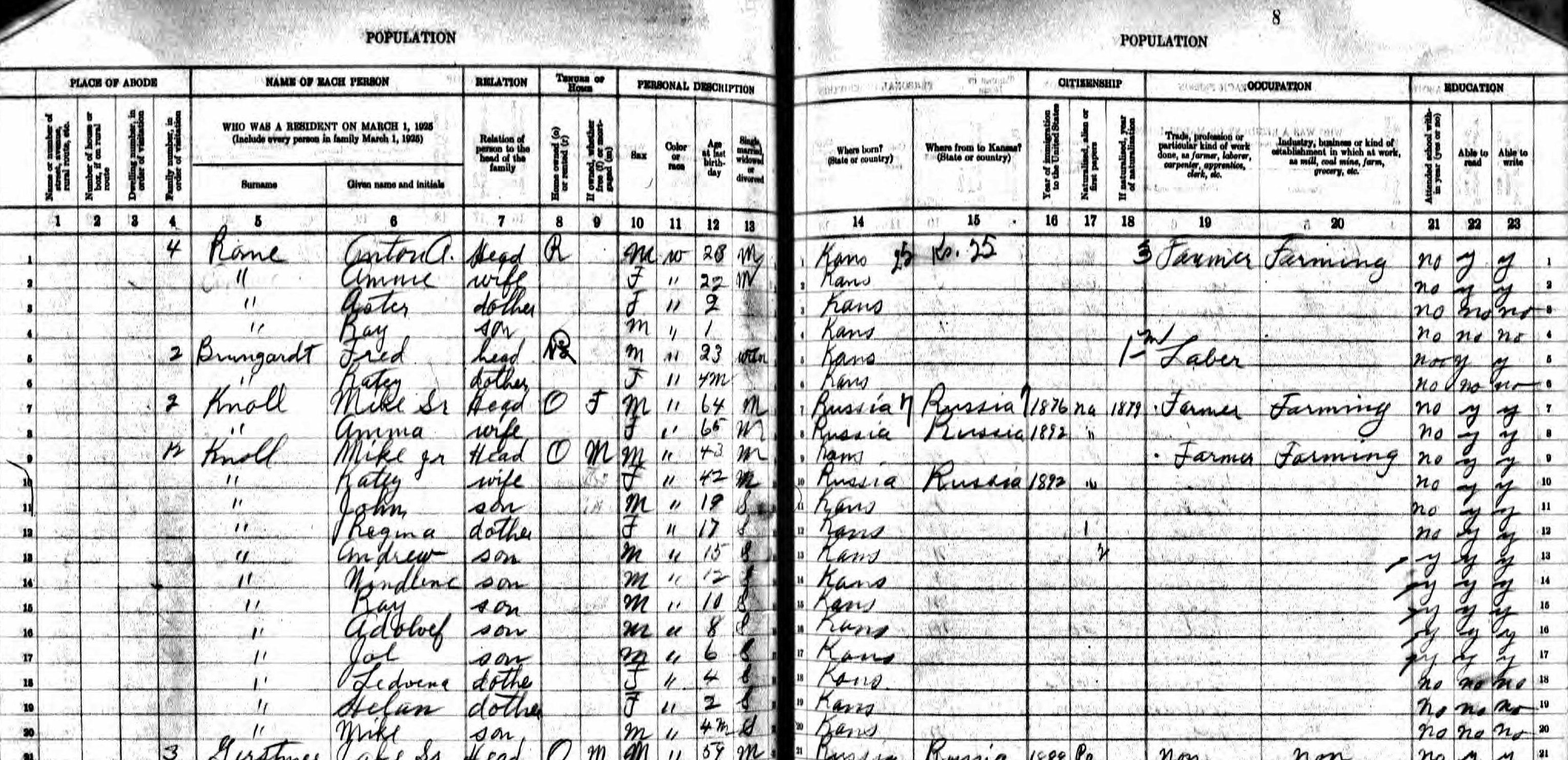

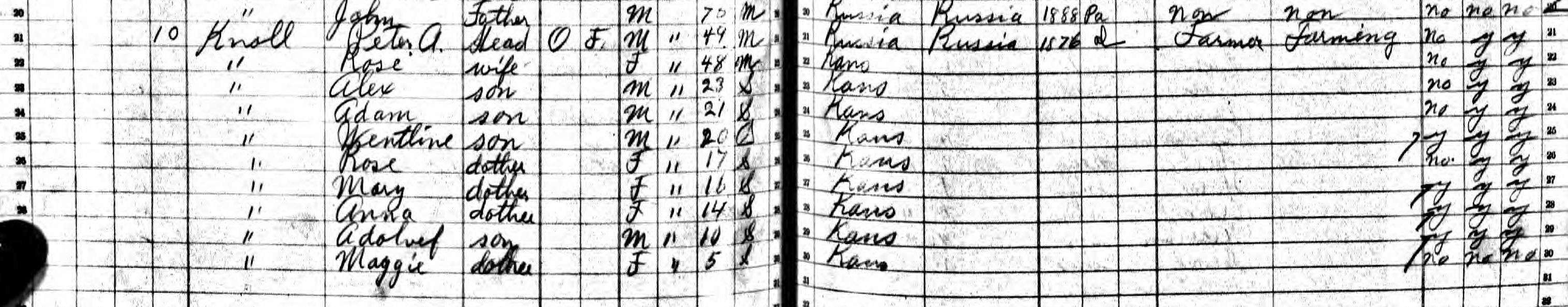

1920

Bryant, Graham, Kansas

Year: 1920;

Census Place: Bryant,

Graham, Kansas;

Roll: T625_533;

Page: 5A;

Enumeration District: 51

Year: 1920;

Census Place: Bryant,

Graham, Kansas;

Roll: T625_533;

Page: 9A;

Enumeration District: 51

Year: 1920;

Census Place: Bryant,

Graham, Kansas;

Roll: T625_533;

Page: 5B;

Enumeration District: 51

Year: 1920;

Census Place: Bryant,

Graham, Kansas;

Roll: T625_533;

Page: 5A;

Enumeration District: 51

Victoria, Ellis, Kansas

Year: 1920;

Census Place: Victoria,

Ellis, Kansas;

Roll: T625_531;

Page: 5A;

Enumeration District: 27

Source: Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. (NARA microfilm publication T625, 2076 rolls). Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

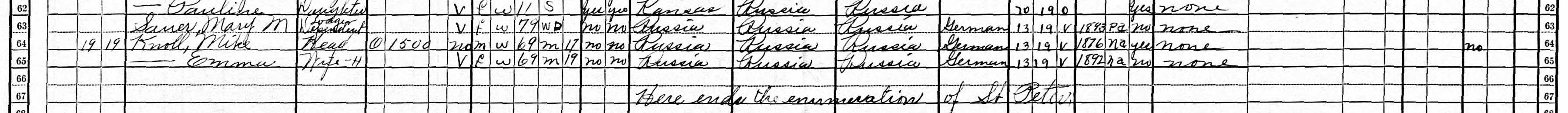

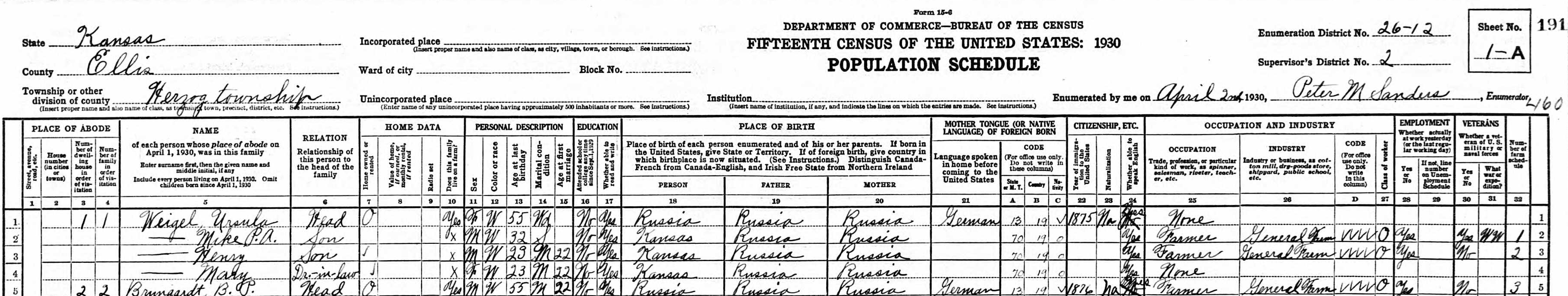

1930

Bryant, Graham, Kansas

Year: 1930;

Census Place: Bryant,

Graham, Kansas;

Page: 10B;

Enumeration District: 0002;

FHL microfilm: 2340438

Year: 1930;

Census Place: Bryant,

Graham, Kansas;

Page: 10A;

Enumeration District: 0002;

FHL microfilm: 2340438

Year: 1930;

Census Place: Bryant,

Graham, Kansas;

Page: 10A;

Enumeration District: 0002;

FHL microfilm: 2340438

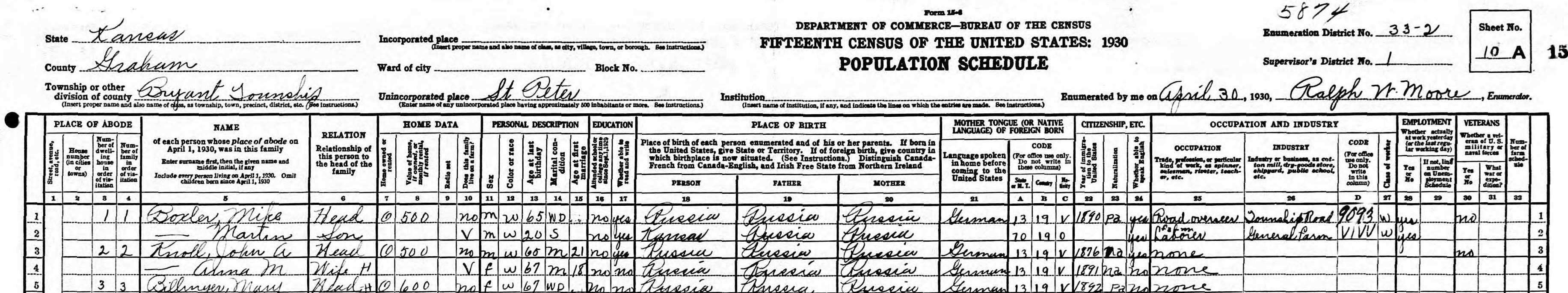

Herzog, Ellis, Kansas

Year: 1930;

Census Place: Herzog,

Ellis, Kansas;

Page: 1A;

Enumeration District: 0012;

FHL microfilm: 2340436

Source: United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930. T626, 2,667 rolls.

1940

Bryant, Graham, Kansas

Year: 1940;

Census Place: Bryant,

Graham, Kansas;

Roll: m-t0627-01233;

Page: 61A;

Enumeration District: 33-2

Year: 1940;

Census Place: Bryant,

Graham, Kansas;

Roll: m-t0627-01233;

Page: 6B;

Enumeration District: 33-2

Source: United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1940. T627, 4,643 rolls.